Author:TANAKA, Atsuko (田中敦子)

Tamba, surrounded by verdant mountains like folding screens, secluded within the hills...

It must be because my destination is Aogaki Town in Tamba, Hyogo, a place known for its hand-woven fabric, that I recall a passage where Prince Yamato Takeru reminisces about his homeland of Yamato. The mountains, lush and enriched by the rainy season, resemble blue barriers. In this mountainous land, Tamba fabric was woven and distributed from the Edo to the Meiji period, only a brief time before it abruptly fell out of favor. It's almost as if this textile was destined to become a phantom. Yet, thanks to discerning eyes and passionate efforts to revive it, this fabric breathes anew and continues to be woven. Eager to know its story, I drive along the highway.

Tamba-nuno, as loved by Yanagi Soetsu.

Several years ago, a friend showed me a bolt of Tamba-nuno. The fabric was produced by the Tamba-nuno Revival Association, established in 1954 under the guidance of Rokuro Uemura, a figure who could be called a scholar of dyeing and weaving among the members of the Mingei movement. Recently, this fabric came into my possession.

It reminded me of Keita Motoji, current director of Ginza Motoji. When he had just joined his family company nearly 15 years ago, he was strongly drawn to bolt of Tamba-nuno that had just come into the store. I had heard that he had been working with Tamba-nuno producers for about eight years, and I had a feeling a Tamba boom was on the horizon. "I should show this fabric to Keita," I thought.

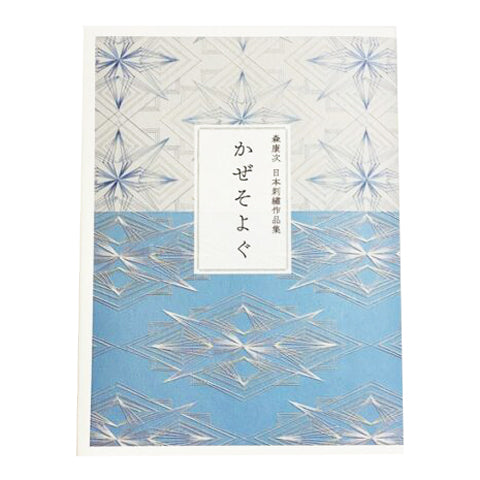

"This is..." Keita said, quickly turning and rushing to a bookshelf. He brought back a large, heavy book. It was a Shimacho, or a book of Tamba-nuno samples, published in 1964 and authored by Rokuro Uemura. One of the limited edition of 280 copies. Inside, 50 pieces of precious Tamba-nuno are affixed.

"There might even be the same one," he mused with a mix of expectation and the thrill of a treasure hunt, his hands pausing as he turned the pages. After slowly poring over the book together, there it was, the same stripe. The pattern from the fabric in the book matched my Tamba-nuno like a puzzle piece.

"So, this is the kind of fabric that was woven at the time. And this year happens to mark the 70th anniversary of its revival," Keita said with rising enthusiasm. What a coincidence. Tamba-nuno suddenly felt much closer.

Tamba-nuno is woven into stripes and checks using plant-based dyes in shades of brown, blue, and green. Silk weft threads, woven in sporadically, faintly sparkle within the warm cotton. A simple textile, yet nowhere else does one find fabric handwoven with handspun silk and cotton thread.

Tamba-nuno is characterized by four key features: it begins with handspun cotton threads, dyed using natural plant dyes like indigo and chestnut. The fabric is then carefully handwoven, and silk threads drawn from waste cocoons are incorporated.

This cloth had been 'discovered' by Soetsu Yanagi, the leader of the Mingei movement, at a morning market in Kyoto during the late Taisho to early Showa period."

(Excerpt) What surprised us at this morning market was something commonly referred to as Tamba-nuno, which the elderly women simply called Tamba. As we later understood, this is a cotton fabric produced in the Saji region of Tamba Province, locally known as Shimanuki. Its characteristic feature is the inclusion of undyed white threads in the weft at intervals.

This is an excerpt from Shūshū Monogatari (蒐集物語) written by Yanagi in 1955. What astonished Yanagi about this fabric was its subdued color, the warmth of the weave, and the beauty of its stripes and checks. Rather than summarizing, it would be better to quote his own words to convey this.

(Excerpt) It was so rich in flavor that it seemed as though it had been specially ordered by tea masters. I was greatly captivated by this fabric when I first saw it and bought it whenever I came across it. This Tamba-fu was circulated at the Kyoto morning market because people in the Keihan area liked to use it as futon covers. Occasionally, it was used for padded kimono, but mostly for duvet and mattress covers. Now, it has become outdated, and as it turns into worn-out clothing, it finds its way to the market. It is said that it was most actively woven from the end of the Edo period to the beginning of the Meiji era.

In other words, by the time Yanagi discovered it, it was already a fabric of the past. The mountainous Tamba region had long been connected to the capital as an important hub of rivers and highways. The fact that Tamba-fu was woven there was largely due to its proximity to Kyoto and Osaka, the major consumption areas. However, since it was a commercial product rather than for personal use, it was quickly surpassed by cheap machine-made cotton fabrics that entered circulation after the Meiji Restoration.

Tamba is a cold region, unsuitable for cotton cultivation. Mr. Uemura speculates in "Tamba-nuno Shima-cho" that Tamba-nuno was likely promoted by the feudal lord during a time when there was a high demand for cotton fabric. It is also suggested that it was influenced by the cotton and cotton fabrics available in Banshu, which lies downstream along the river. The brownish shades are dyed using local plants like chestnut skins, Kobuna grass, and alder. The indigo color can also be dyed in various shades by dyers. Being a sericulture area, Tamba-nuno also incorporates weft threads made from waste cocoons. Hand-spun yarn with a soft twist creates richly flavored stripes in a simple plain weave. Within this weave lies the "elegance of wildflowers from the mountains and fields."

(Excerpt) Those who will compile the history of Japanese cotton fabrics in the future must not forget the existence and value of this fabric. Perhaps the day will come when it is praised as a new classic textile. Incidentally, I should mention that this fabric, which had been out of production for over half a century, has recently seen efforts for revival centered around Daito-ji Temple near Saji in Hikami-gun, Tamba Province. Spinners, dyers, and weavers have come together to restore it, once again.

Yanagi first introduced Tamba-nuno to the world in 1931 in the sixth issue of the magazine Kogei, the official publication of the Mingei movement. This brought attention to Tamba, attracting many enthusiasts and leading local people to take pride in their traditional fabric. This feature played a huge role in the revival of the craft.

Fostered by Nature and History

The fabric is woven rhythmically by hand, ensuring the edges are woven neatly and the weft threads are pounded in.

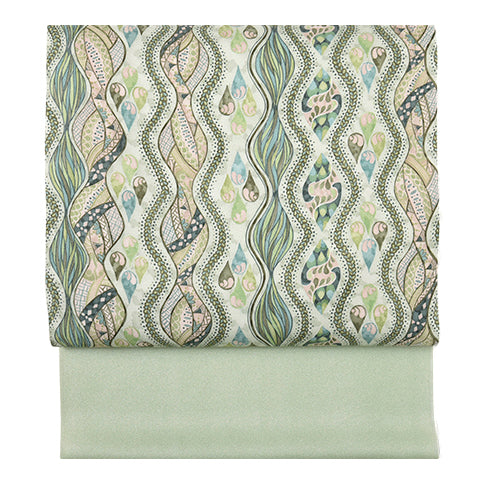

名古屋帯

名古屋帯

袋帯

袋帯

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

浴衣・半巾帯

浴衣・半巾帯

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

肌着

肌着

小物

小物

履物

履物

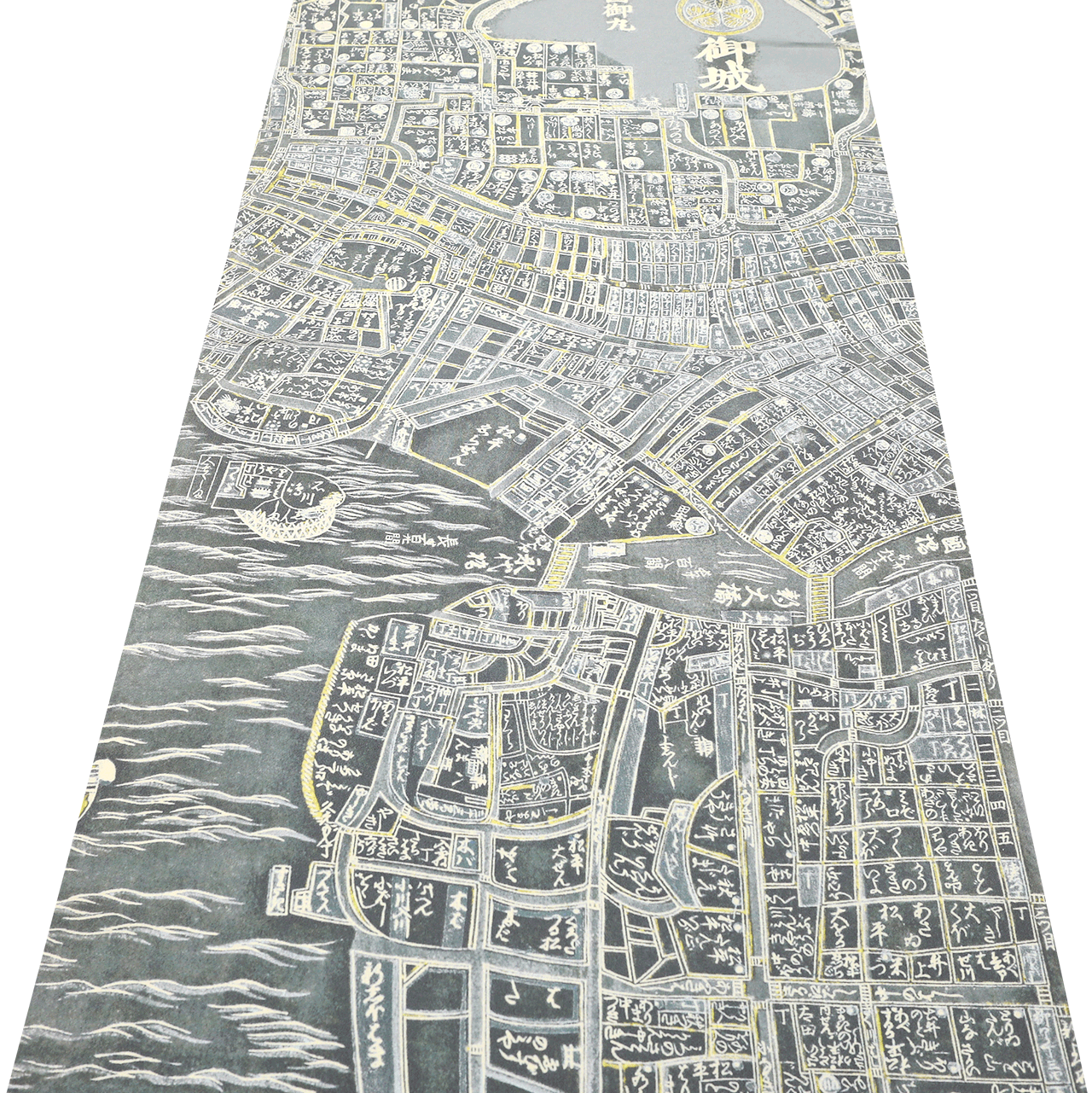

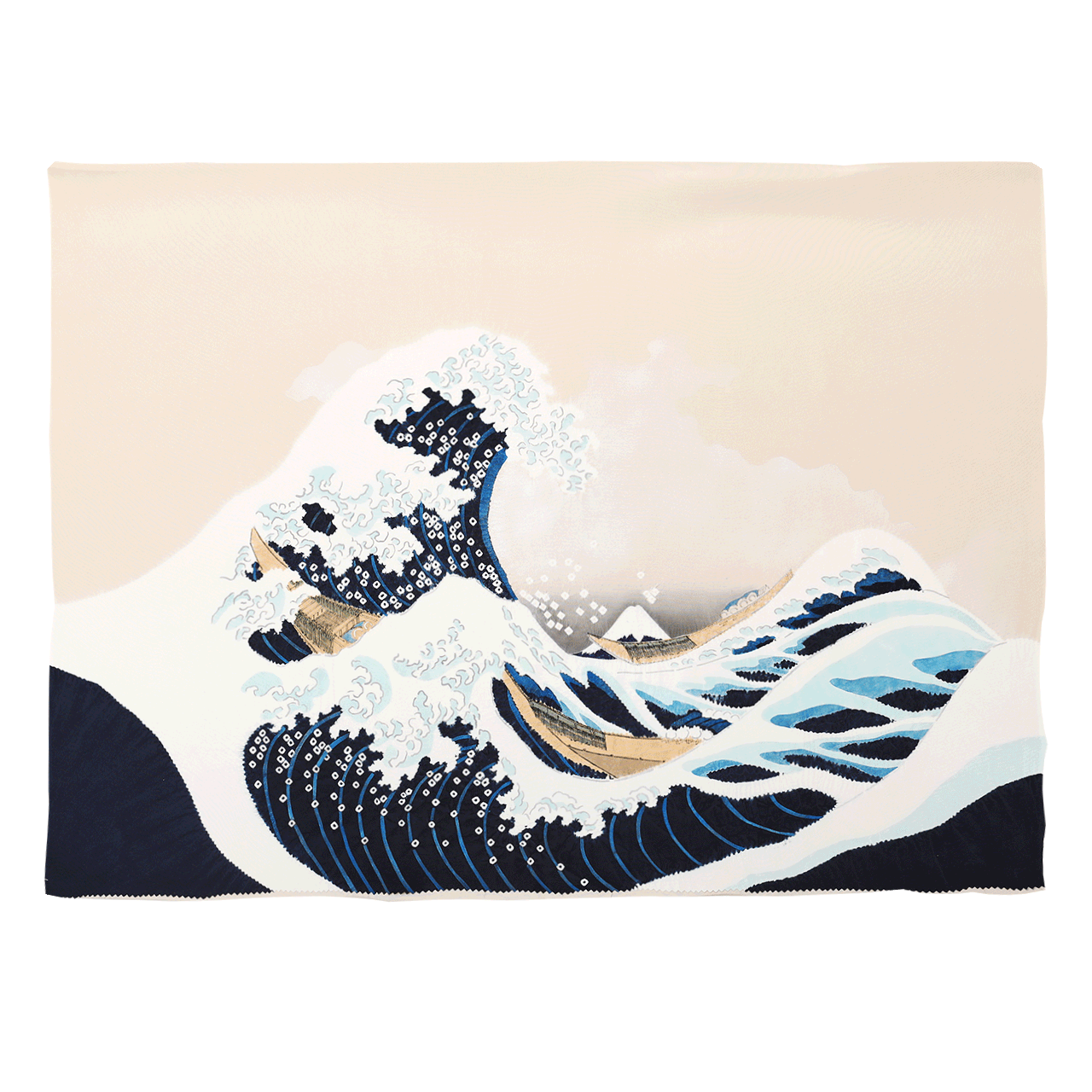

書籍

書籍

長襦袢

長襦袢

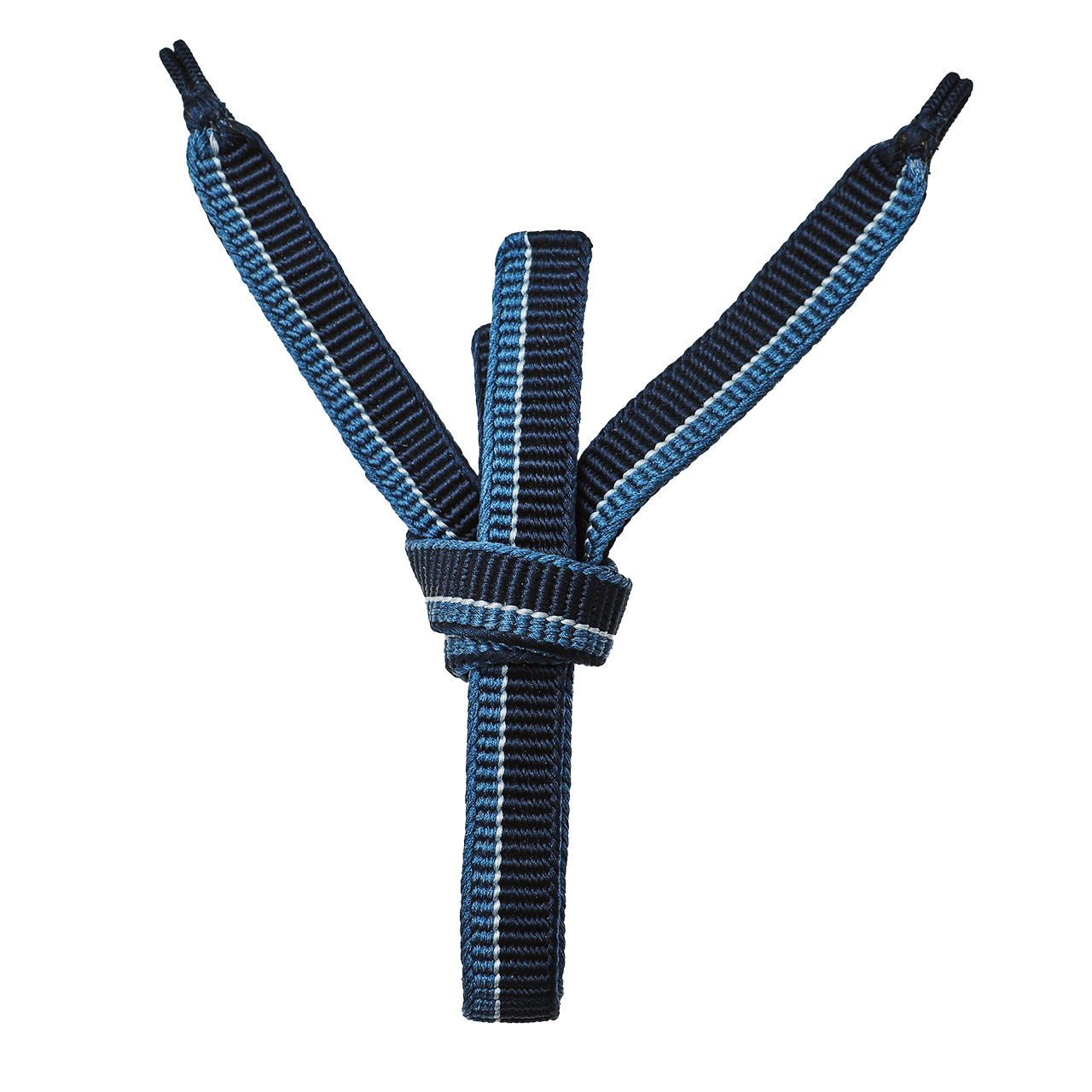

小物

小物

帯

帯

お召

お召

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

袴

袴

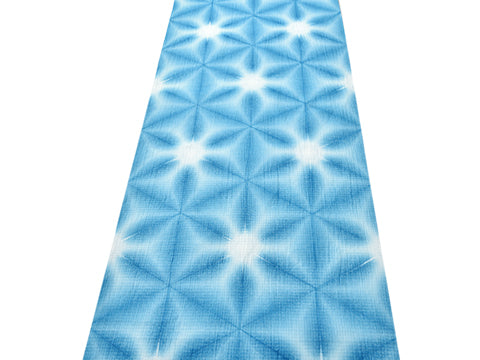

長襦袢

長襦袢

浴衣

浴衣

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

額裏

額裏

肌着

肌着

履物

履物

紋付

紋付

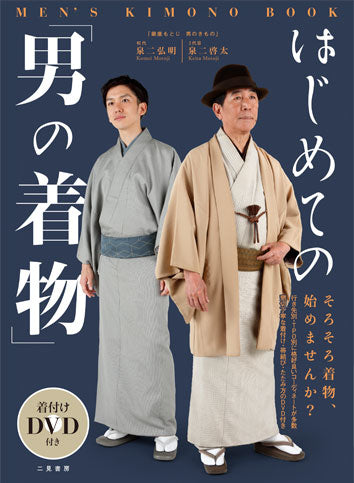

書籍

書籍