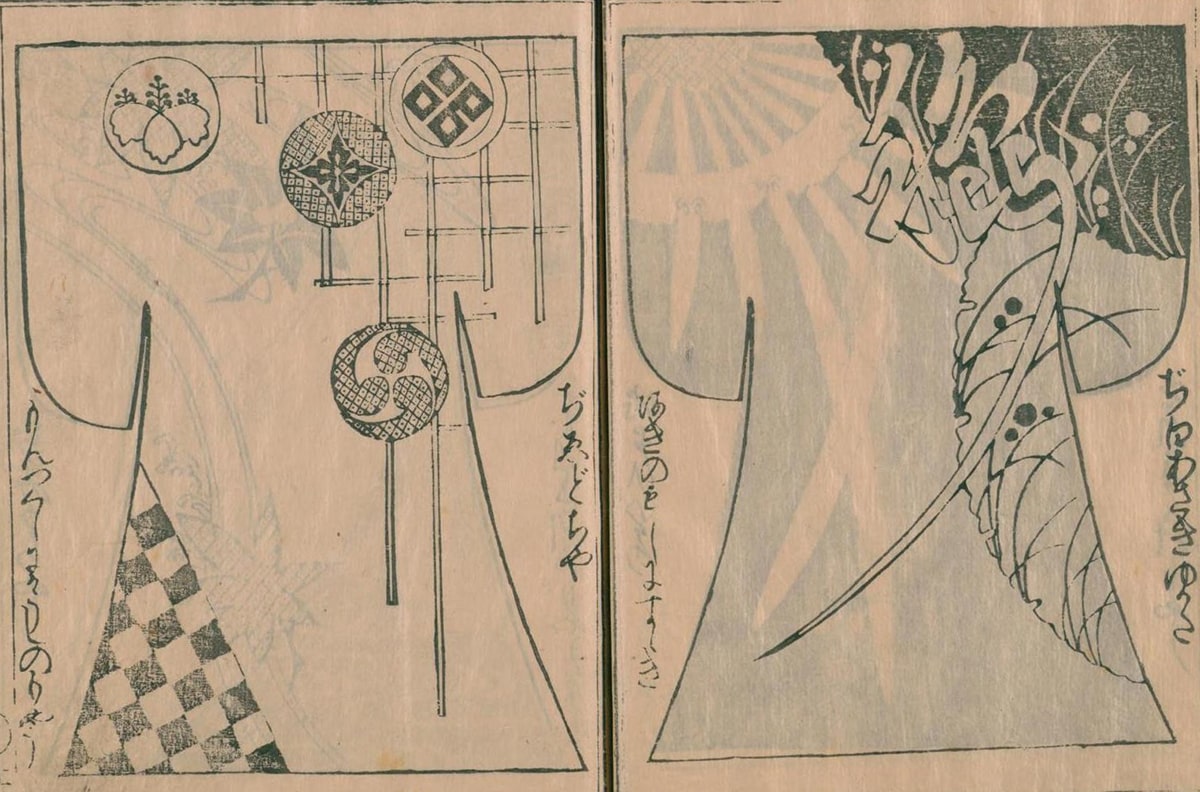

The first pattern book for kosode designs, titled "Shinsen Gohiinagata" published in the 6th year of Kanbun (1666).

The precursor to the modern kimono, known as kosode, originally served as practical attire for commoners and was also worn as an undergarment by the aristocracy. However, around the Muromachi period, it evolved into the primary clothing for both men and women of all classes. During the Sengoku period to the early Edo period, a fashion system centered around the kosode began to take shape.

One of the most distinctive features of the kosode is its straight-line construction, creating a continuous form from top to bottom. While there were slight variations in sleeve length, width, and overall length over different eras, the kosode remained generally flat and lacked the three-dimensional decorations like buttons, pockets, pleats, or slits seen in Western clothing.

This simple kosode design provided a perfect canvas to express the unique, expressive designs, leading to significant fashion evolution throughout the Edo period. It generated a wide range of patterns and intricate techniques that stood out globally, laying the foundation for the present-day kimono culture.

So, what were the changes that the kosode underwent during the approximately 260 years of the Edo period? Let's explore its transformation by deciphering the trends in patterns, composition, and motif throughout different eras during this period.

Early 17th Century : Keicho Kosode

The Keicho Kosode refers to a style of kosode that evolved from the attire of samurai-class women during the Momoyama period. Strictly speaking, it refers to the style that became popular towards the end of the Keicho era.

Until the Momoyama period, kosode designs were primarily characterized by symmetrical design compositions, often featuring patterns only on the shoulders and hem ("katashita" and "susomawari"), or alternating designs on each shoulder ("katamiginuwari"), or even designs divided into sections on the upper, lower, left, and right sides ("dangawari").

Stitched Brocade: Red and White Checker, Zig-Zag Bridge, Willow trees

(Important Cultural Property/Tokyo National Museum)

16th century, Azuchi-Momoyama period

However, in the early Edo period, during the Keicho era, kosode took on a different style compared to previous generations. There emerged sections with dynamic elements such as cloud and mountain shapes. The background was no longer merely a backdrop but often played a role as a pattern that contributed to the overall design.

Stitched Brocade: Light Blue and White Rectangular Gauze with Waves and Poetry Patterns The Metropolitan Museum of Art

16th to 17th century, Azuchi-Momoyama to Edo period

During this period, kosode were dyed using shibori, stencil dyeing, and often richly embroidered. Elaborate and vibrant designs depicting various patterns including landscapes, flowers, and birds were common. Some garments were so densely decorated that the fabric underneath was hardly visible, and these are also referred to as ji-nashikosode meaning fabric-less kosode.

Kosode: Black and Red Dyed Herringbone Silk with Pine Bark and Floral Patterns

Important Cultural Property/Kyoto National Museum Early Edo period

Late 17th Century:Kanbun Kosode

Furisode of White Rinzu (satin damask) with chrysanthemum and small flowers.

Tokyo National Museum

17th Century, Edo Period

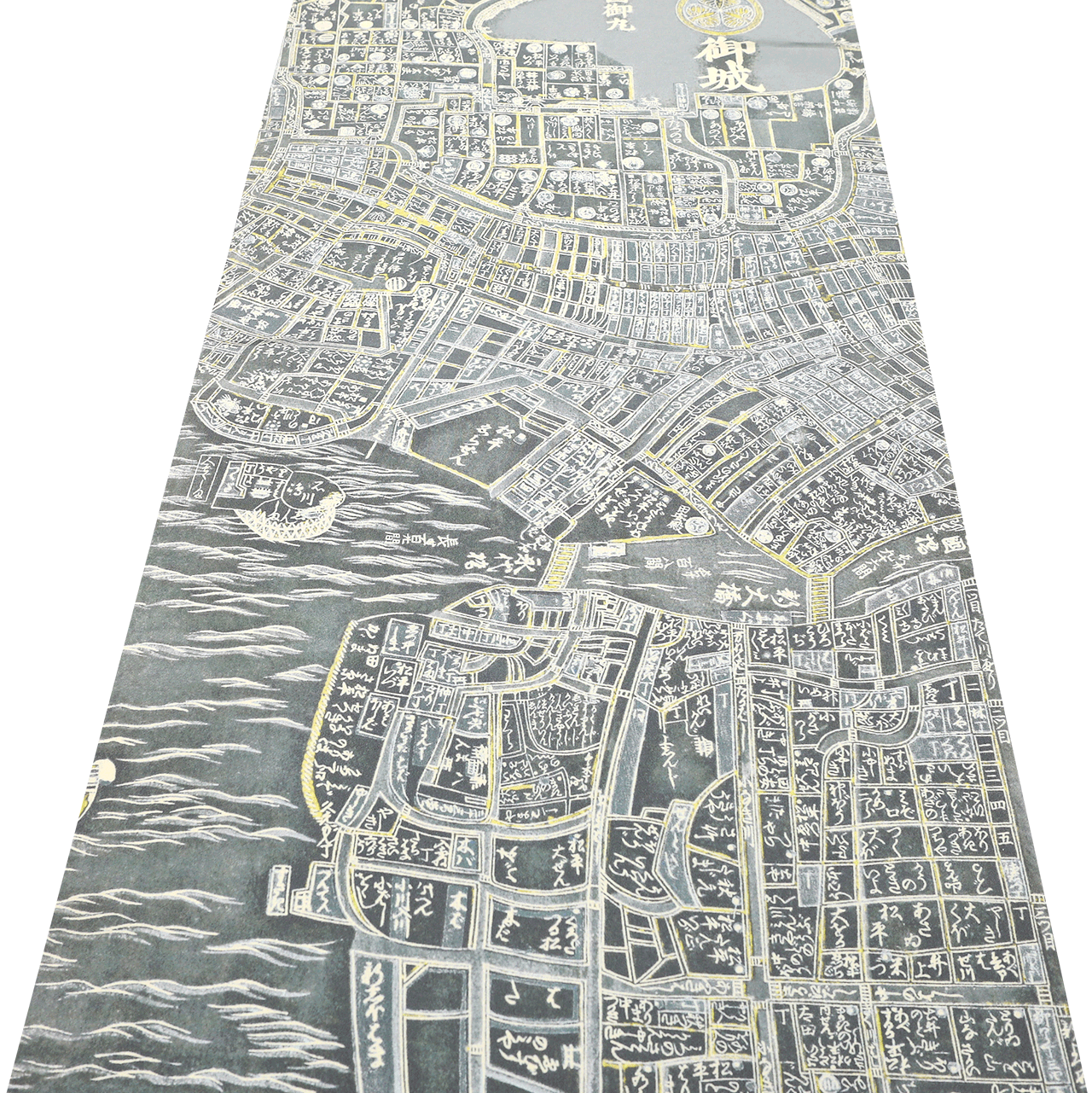

The kosode depicted in Tofukumonin Masako's (The wife of Emperor Go-Mizuno) order book Gankin-ya hinagata chou, published in 1661, and in the first kosode pattern hinagata book Shinsei goiinagata, published in 1666, are not jinashi, which was the norm until then. The patterns started at the left shoulder, go down through the right shoulder to the right hem, and are often blank around the left body. The pattern often has a blank space around the left side of the body. This is a characteristic of Kanbun kosode, and shows a change from the compositional patterns of previous generations to a more dynamic, pictorial pattern.

Shinsen-Ohiinagata

National Diet Library

Furthermore, the motifs of the patterns became more diverse. In addition to depictions of flowers, birds, the changing seasons, and objects, there emerged allegorical designs inspired by classical texts, Noh theater, and traditional songs. Even when representing elements of nature, the approach shifted from straightforward realism to introducing twists and aiming for intriguing interpretations, resulting in patterns that offered a high degree of creative freedom and often wit too.

In terms of techniques, shibori, kasuri, embroidery were common. To embellish, gold wrapped threads couched onto the exterior of the fabric become popular as opposed to gold leaf for metallic accents.

Early 18th Century:Genroku Kosode

White Chirimen (crepe) Silk Kosode with Paulownia and checkerboard pattern

(Tokyo National Museum) Genroku Era (18th century)

The Enpō to Genroku period marked a time when the merchant class, who began to accumulate economic power after the Great Fire of Meireki, gradually became cultural influencers, replacing the samurai class. Luxurious kosode, once exclusive to the samurai class, began to spread among the affluent townspeople. Wealthy merchant wives engaged in a competition of opulence through a practice known as Date-Kurabe, where they showcased their elaborate outfits. This trend became excessive to the extent that some merchant families faced confiscation of their properties.

To curb the extravagance spreading among these townspeople, multiple edicts were issued, and by the late 17th century, production, sale, and wearing of techniques like costly techniques such as shibori, kinshi (gold embroidery), and stitched brocade (nuihaku) were prohibited. However, as suggested in Honcho Niju-Fuko "The rules are observed outwardly, but various methods are used in secret,"

During this period, kosode retained the characteristics of the Kanbun era, with features such as embroidery and shibori, but transitioned from patterns located around the right shoulder to all-over designs. These elaborately crafted garments catered to the ornamentation desires of prosperous townspeople, offering a transition from the right-shoulder patterns of earlier times to more comprehensive designs.

Kosode: White Rinzu Silk with Plum Tree and Bamboo Fence Patterns

(Tokyo National Museum) Edo period, 18th century

In response to the restrictions imposed by the edicts, the kosode industry enthusiastically developed new techniques to circumvent the rules. One of the most notable innovations was the technique of yuzen dyeing. Through a dyeing technique that involved applying resist paste and intricate color applications, patterns could be achieved that were previously unattainable with just embroidery or shibori. During this time, the primary technique for creating kosode patterns gradually shifted from embroidery and shibori to yuzen.

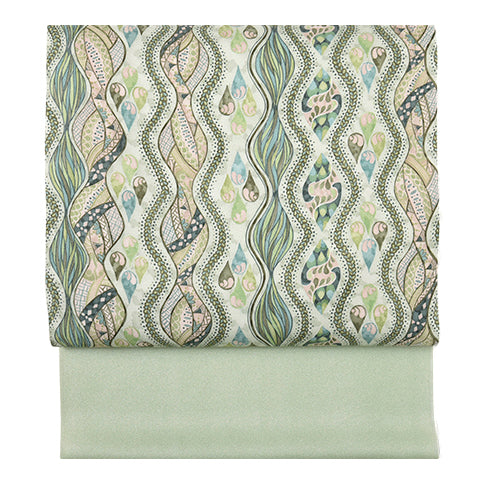

Furthermore, yuzen makers garnered attention not only for their techniques but also for their newly popular motifs known as yuzen moyo. Among these, the maru (circle) motif gained particular prominence. Often featuring flowers, grasses, and other natural themes, this motive was celebrated for its modern yet timeless appear.

Yuzen Hiinagata Gosho-miyage Konomasu Volume 1

(National Diet Library)

During this period, Kakie, or hand-drawn kosode were also extremely popular. The artist would directly paint the patterns onto the fabric creating their work of art. Unlike yuzen, painting directly onto the fabric creates a sense of spontaneity. This one-of-a-kind nature of these garments attracted those who sought distinction in clothing. This trend was embraces among the upper classes in particular, and works created by artists like Ogata Korin and Sakai Hōitsu are still preserved to this day.

Kosode of white twill with handpainted autumn grasses - Ogata Korin

Important Cultural Properties of Japan, Tokyo National Museum

18th Century Edo Period

Mid to Late 18th Century:Horeki and Tenmei Kosode

Kosode in Light Blue Silk Chirimen (crepe) with Seashore and Plover, Lyric and Text Patterns

(Tokyo National Museum) 18th century, Edo period

Until the Genroku era, the economic and cultural leaders were primarily centered in the Kyoto-Osaka region. However, from the Horeki to Tenmei periods, a flourishing of merchant culture began in Edo (modern-day Tokyo). During this time, kosode designs transitioned towards simplicity, reflecting the frugal spirit encouraged by the Kyoho Reforms. The Kyoho Reforms were a set of changes made in 18th-century Japan by the ruling Tokugawa shogunate to stabilize the economy, including improving the currency, adjusting taxes, regulating trade, and strengthening social order.

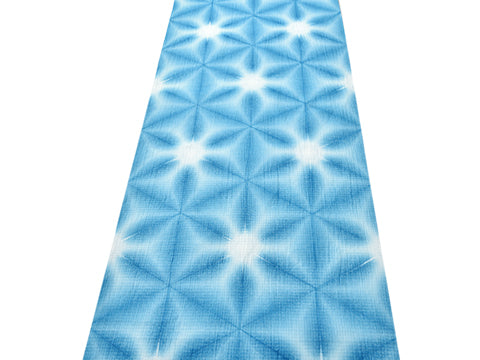

Drawing on techniques like shiro-age, a form of yuzen where white lines of resist construct a delicate pattern, were combined with embroidery to create kosode with fine, scattered patterns. The use of patterns limited to the hem or collar also became more prevalent, aligning with the minimalistic sensibilities which were emerging.

Hagi no Tamagawa by Suzuki Harunobu

(The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

As the patterns on kosode became more subdued, there was a proportional increase in the prominence of the obi . Up until then, the primary function of the obi had been to secure the kosode and prevent it from opening, and it had played a practical role rather than serving as a decorative accessory. However, around the late 17th century, obis gradually grew wider and longer, and the variety of fabrics used for obis diversified. Various styles of tying obis also emerged, and by the mid-18th century, the situation shifted to one where the obi played a more dominant role in the ensemble.

Spring Stroll in Mukojima by Torii Kiyonaga (Tokyo National Museum)

18th century, Edo period

Early 19th Century Bunka/Bunsei Kosode

A long sleeved furisode kimono made of habutae silk in light blue depicting the harvesting of tea leaves.

Tokyo National Museum 19th Century Edo Period.

The later years of the Edo period marked a period of maturity for merchant culture, and it's during this time that the sophisticated culture that we commonly associate with the period emerged.

Accelerated by the Kansei Reforms, the refined sensibilities nurtured by wealthy merchants in Edo began to permeate the general populace. Kosode patterns became even more detailed than those of the pre-Kansei period, and designs depicting landscapes with a sense of realism also emerged. Colors such as rich variations of brown, gray, and indigo, collectively known as Shijuhachi-cha Hyakunezumi or "48 browns and 100 greys" were established as the colors in vogue, defining the era.

This era is often regarded as the height of Edo-period refinement, where the culture of iki (sophistication) associate with the Edo period flourished.

Multicolor Ukiyo-e Yanebuneyotsuami by Kitagawa Utamaro

(Tokyo National Museum)

Due to strict sumptuary laws, people channeled their aesthetic desires into their undergarments and linings; luxurious shibori nagajuban (underkimono) and kasuri patterned kimono linings were used, and an aesthetic was found in subtle fashion statements like the collar and hem peeking out.

Kasuri Sarasa Nagajuban (Kyushu National Museum)

Origin: Japan, Fabric: Coromandel Coast, India 18th to 19th century

While the kimono of the late Edo period might not possess an outwardly glamorous appearance, it expresses its commitment to refinement through intricate craftsmanship with details where you may not expect to find them.

In conclusion,

Within the Edo period, the kosode was transformed from a humble garment into a form of fashion and personal expression. Remarkably, the kosode was not just reserved for upper classes, but its development was driven by people of multiple socioeconomic strata, resulting in diverse patterns and techniques throughout the country. This is also one of the factor which resulted in this rich textile culture to not just survive but thrive, and be inherited from generation to generation.

【References】

「KIMONO」(Tokyo National Museum)

「Life of Kimono and Yukata in Edo」Maruyama Nobuhiko(Shogaku-kan)

「Senshoku no Bi 21 Volume 1;Kosode of Edo」(Kyoto-Shoin)

名古屋帯

名古屋帯

袋帯

袋帯

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

浴衣・半巾帯

浴衣・半巾帯

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

肌着

肌着

小物

小物

履物

履物

書籍

書籍

長襦袢

長襦袢

小物

小物

帯

帯

お召

お召

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

袴

袴

長襦袢

長襦袢

浴衣

浴衣

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

額裏

額裏

肌着

肌着

履物

履物

紋付

紋付

書籍

書籍