Nowadays, you will see it less and less, but in the 1960s and 1970s, a black haori was almost ubiquitous among women at school ceremonies and graduations. They often paired their black haori, or kurobaori, with iro-muji or edo-komon kimono, creating a distinctive look that was observed nationwide.

This raises the question: why did black haori become so common across Japan for these formal events?

Today we will take a look into the history of not only the kurobaori, but also the history of haori in womenswear too.

The History of Haori in Womenswear.

CHOBUNSAI, Eishi - Geisha of Fukugawa

(New York Public Library - Stephen A. Schwarzman Building)

A Symbol of Social Progess

Modern Beauty, MIZUNO, Toshikata / 国立国会図書館デジタルコレクション)

The popularity of women's haori experienced a temporary decline due to prohibitions, but signs of revival appeared around the Bunka era (1818-1830), and their numbers surged during the Meiji era.

Initially used primarily for warmth, haori gained popularity as casual formalwear for women around the Meiji period. Black haori, in particular, became widespread, often paired with a rounded bun hairstyle, favored by elegant ladies. This style extended to working women, especially female teachers who wore black haori adorned with crests for podium appearances and ceremonial events like graduations. For women with limited opportunities in formal settings, black haori became a symbol of their participation in official occasions, signifying social advancement.

In addition to black, colors like dark purple and indigo were also favored for haori during this period.

Simultaneously, luxurious summer haori made from silk gauze, known as ro-ichiraku, gained popularity among upper-class women. Despite haori traditionally serving as warm clothing, criticism arose against wearing lined silk or gauze haori in summer due to their impracticality for the season.

In modern kimono etiquette, it's generally acceptable to wear haori indoors. However, historically, it was customary to remove haori indoors. Writer Hasegawa Shigure noted, 'During my daughter's time in the mid-Meiji era, haori were worn as substitutes for coats primarily outdoors in cold weather. Respectable daughters and maids from decent households would never wear them indoors. When visiting someone's home, they would remove haori when transitioning from the entrance to the guest room, even if worn initially. Particularly in cold weather among close acquaintances, apologies were made for wearing haori indoors.

Decidedly fashionable in the Taisho era

Shojo Gaho, January Edition, 1926.

Kikuto Iri Archive.

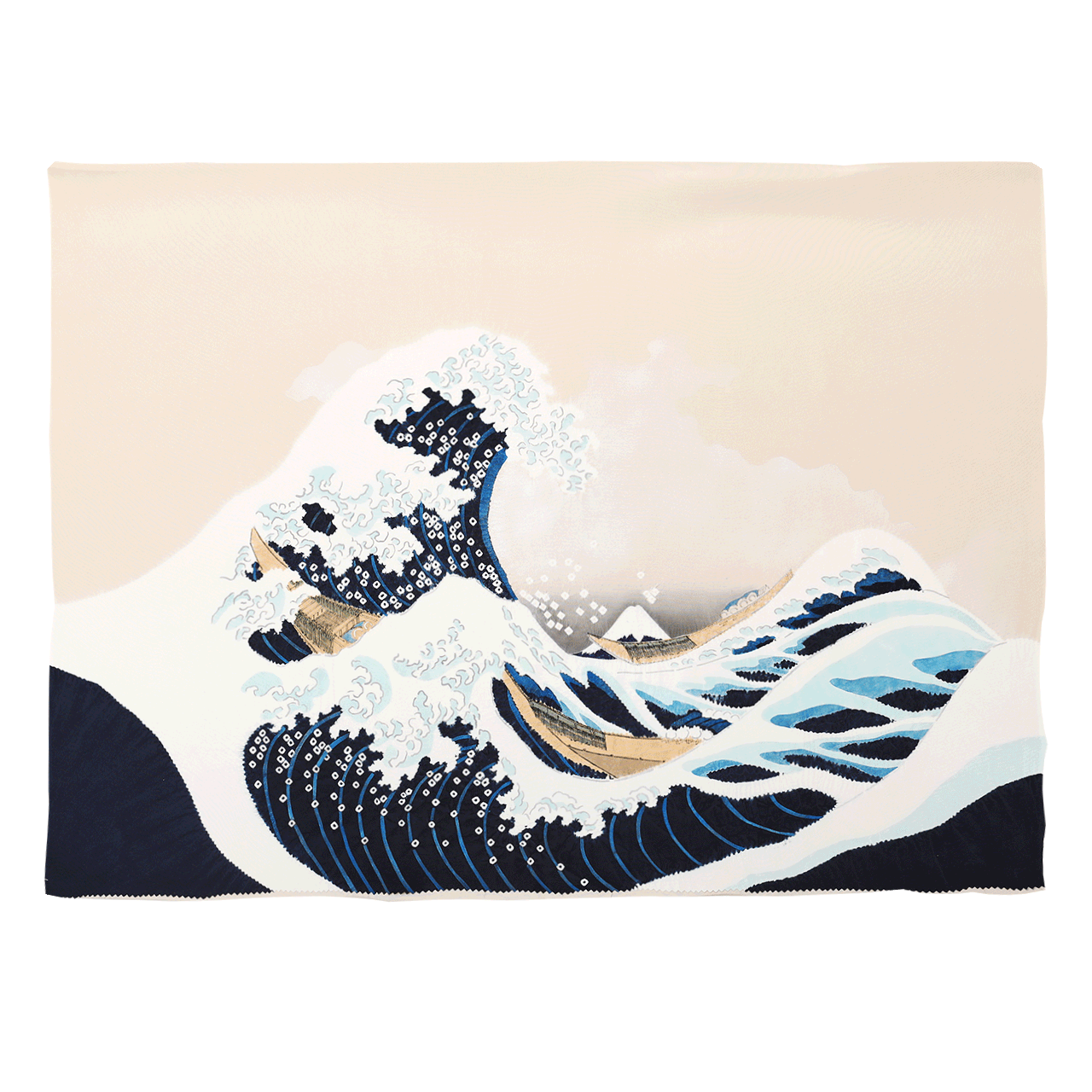

It wouldn't be an exaggeration to say that the Taisho era to early Showa era marked the pinnacle of glamour in the history of kimono fashion. With the widespread use of synthetic dyes, advancements in dyeing techniques, and influences from foreign cultures, numerous colorful and fashionable kimonos and obis were created during this period. Haori were no exception to this trend.

By the Taisho era (1912-1926), haori were not only worn for warmth but also for fashion. Simply wearing a haori could transform an ordinary kimono into a dressier look. Haori were typically quite long, with flashy patterns prevalent in Kansai and more muted patterns in Kanto.

Some wealthy women would wear both a haori and kimono made from the same fabric, using expensive textiles such as Oshima Tsumugi in popular patterns like tatsugo-gara, as well as textiles such as Kihachijo and Meisen. Some women even blended Western and Japanese styles by wearing a haori over their dresses.

Post-war economic growth launches the haori even further.

(The wife of Nobutaka Shiōden wearing a black crested haori. / wikipedia)

"After World War II, the haori underwent a significant transformation from its pre-war style, adopting shorter lengths due to fabric shortages. In the 1950s, designer Sueko Ōtsuka popularized a shorter version known as Chabaori or Osue baori. This innovative design, which concealed the hips and featured bias cutting for enhanced mobility, allowed two haori to be made from a single bolt of cloth. Equipped with pockets for functionality, it was versatile enough to be worn over both kimonos and Western clothing, gaining popularity among both men and women, including the novelist Tsutomu Mizukami.

The resurgence of longer haori came during Japan's period of high economic growth and beyond. By then, haori lengths extended just above the knees, with luxurious "eba haori" often featuring large patterns passing over the seams. Eventually, the iconic black haori emerged as a staple for graduation and entrance ceremonies.

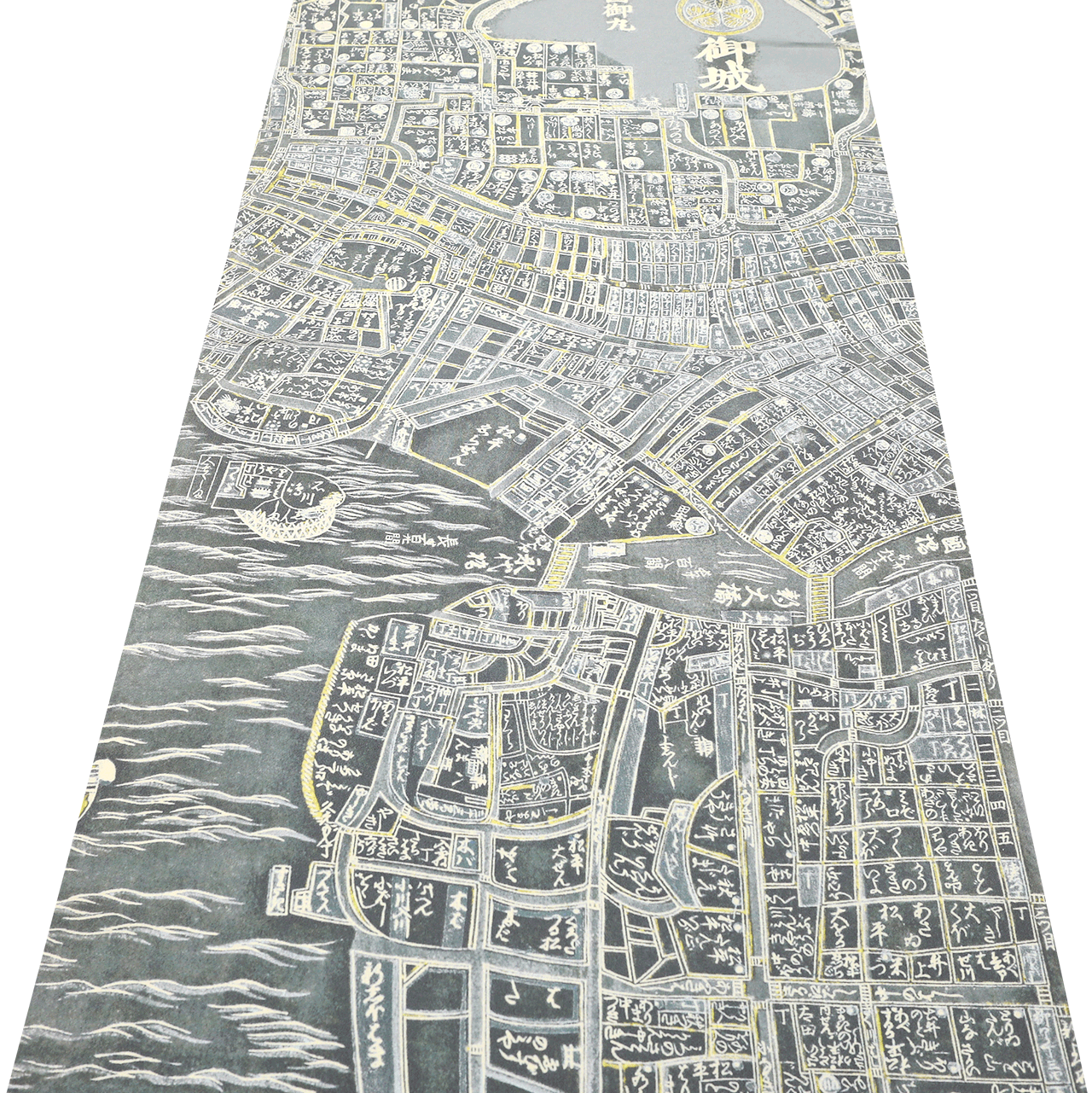

The popularity of black haori can be traced back to Yoshizawa Orimono, a textile manufacturer in Tokamachi, Niigata Prefecture. At that time, manufacturers in Tokamachi wove white fabric on Jacquard looms, which would yellow over time unless dyed. Initially dyed light blue or pink to prevent yellowing, one batch was mistakenly dyed black due to a dyeing error. This unexpected outcome caught the attention of Mr. Soso Hosoda, a buyer for Isetan department store in Tokyo, who decided to sell it, sparking the black haori trend in the Showa era.

Subsequently, black haori adorned with embroidery, shibori (tie-dyeing), hand-painting, and stencil dyeing were introduced by various companies. Beyond providing warmth, these haori were easy to wear and matched any kimono, quickly gaining popularity for their formal appearance akin to black montsuki (formal black kimono with family crests). The trend surged further as part of wedding trousseau items and ceremonial dress, with approximately 11 million black haori produced over about 20 years.

However, from the 1980s onwards, the houmongi for formal occasions outside one's home became more widespread among the affluent, rendering the need to cover the obi less necessary. A decline in mothers wearing kimonos to ceremonies also contributed to the waning popularity of black haori.

Entering the Heisei era, long haori with vibrant patterns gained favor among antique kimono enthusiasts influenced by Taisho Romanticism. Today, haori remains a fashion item combining practicality and ornamentation, primarily for casual wear, adapting to various social influences over time. Why not enjoy a Reiwa-style reinterpretation of women's haori, blending contemporary fashion with its rich historical significance?

【References】

・TOMIZAWA, Kimiko. (2021) Ano Toki no Hayari to "Utsukushi Kimono"

・DAIMARU, Hiroshi. TAKAHASHI, Haruko. (2016) Nihonjin no Sugata to Kurashi Meiji Taisho Showa zenki no Miso.

・KOIZUMI, Kazuko. (2006) Showa no Kimono

・NAKAMURA, Keiko. NAKAGAWA, Haruka. (2018) Antique Kimono Mangekyo Taisho - Showa no otome ni manabu kikonashi.

・MARUYAMA, Nobuhiko. (2007) Edo no Kimono to Ibukatsu

・KIKUCHI, Hitomi. (2011) Edo Isho Zukan

名古屋帯

名古屋帯

袋帯

袋帯

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

浴衣・半巾帯

浴衣・半巾帯

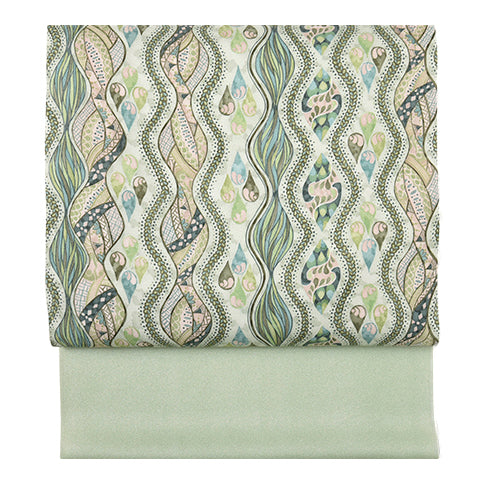

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

肌着

肌着

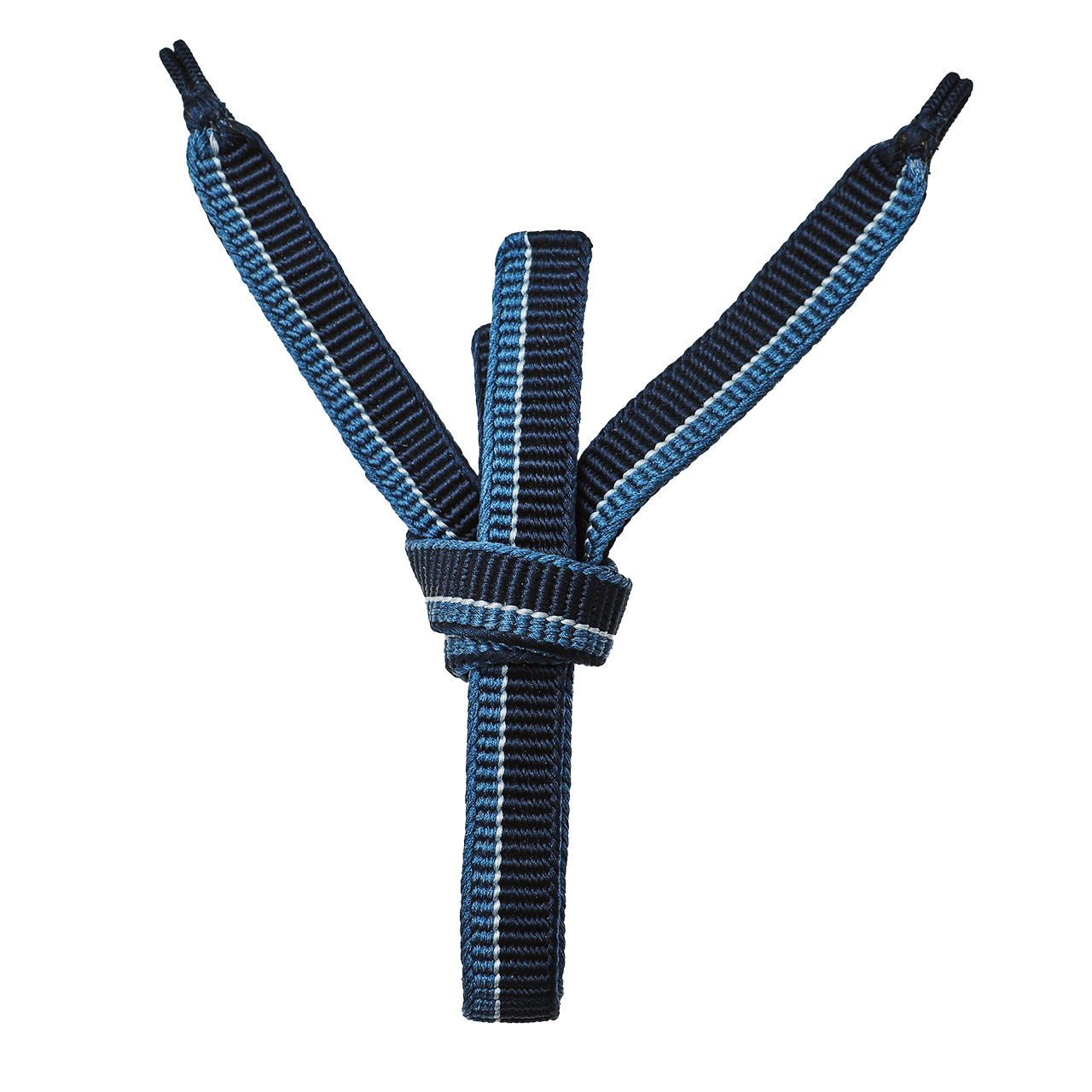

小物

小物

履物

履物

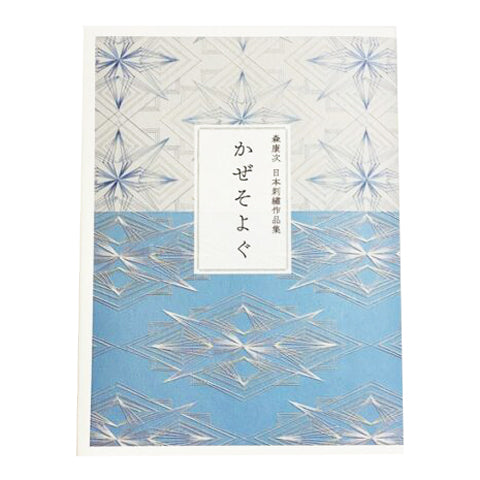

書籍

書籍

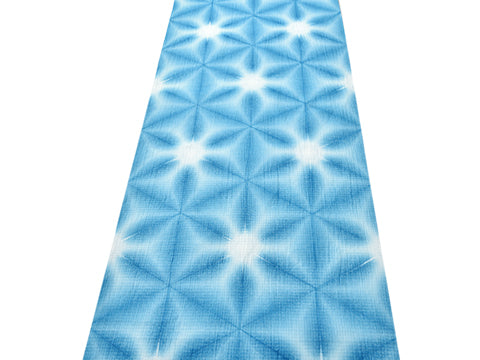

長襦袢

長襦袢

小物

小物

帯

帯

お召

お召

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

袴

袴

長襦袢

長襦袢

浴衣

浴衣

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

額裏

額裏

肌着

肌着

履物

履物

紋付

紋付

書籍

書籍