Photo: SHIOKAWA, Yuya

The Complicated Past, and Bright Future of Yaeyama Joufu

Author:TANAKA, Atsuko

On the shallow beaches of Ishigaki Island, where white sand glows in the sun, several bolts of kasuri-patterned cloth sway gently in the waves.

This is umizarashi (海晒し), or seawater bleaching, part of the traditional finishing process for Yaeyama Joufu (八重山上布). It’s a scene so dreamlike it feels like a mirage, but when you look into its history, the picture darkens. This beautiful tradition overlaps with the hardship faced by the Yaeyama Islands under the rule of the Ryukyu Kingdom, and the contrast between beauty and struggle becomes stark.

One system that can’t be separated from the story of Okinawan textiles is the nintozei, or head tax. During the time when the Ryukyu Kingdom was under the control of the Satsuma domain, the remote islands like Yaeyama and Miyako were forced to pay heavy taxes. All islanders between the ages of fifteen and fifty were required to offer rice, millet, and most notably, cloth.

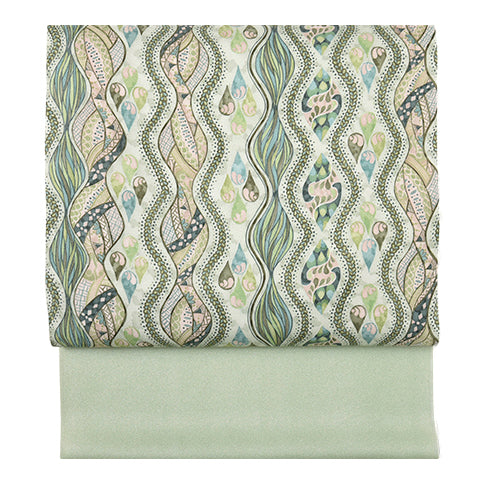

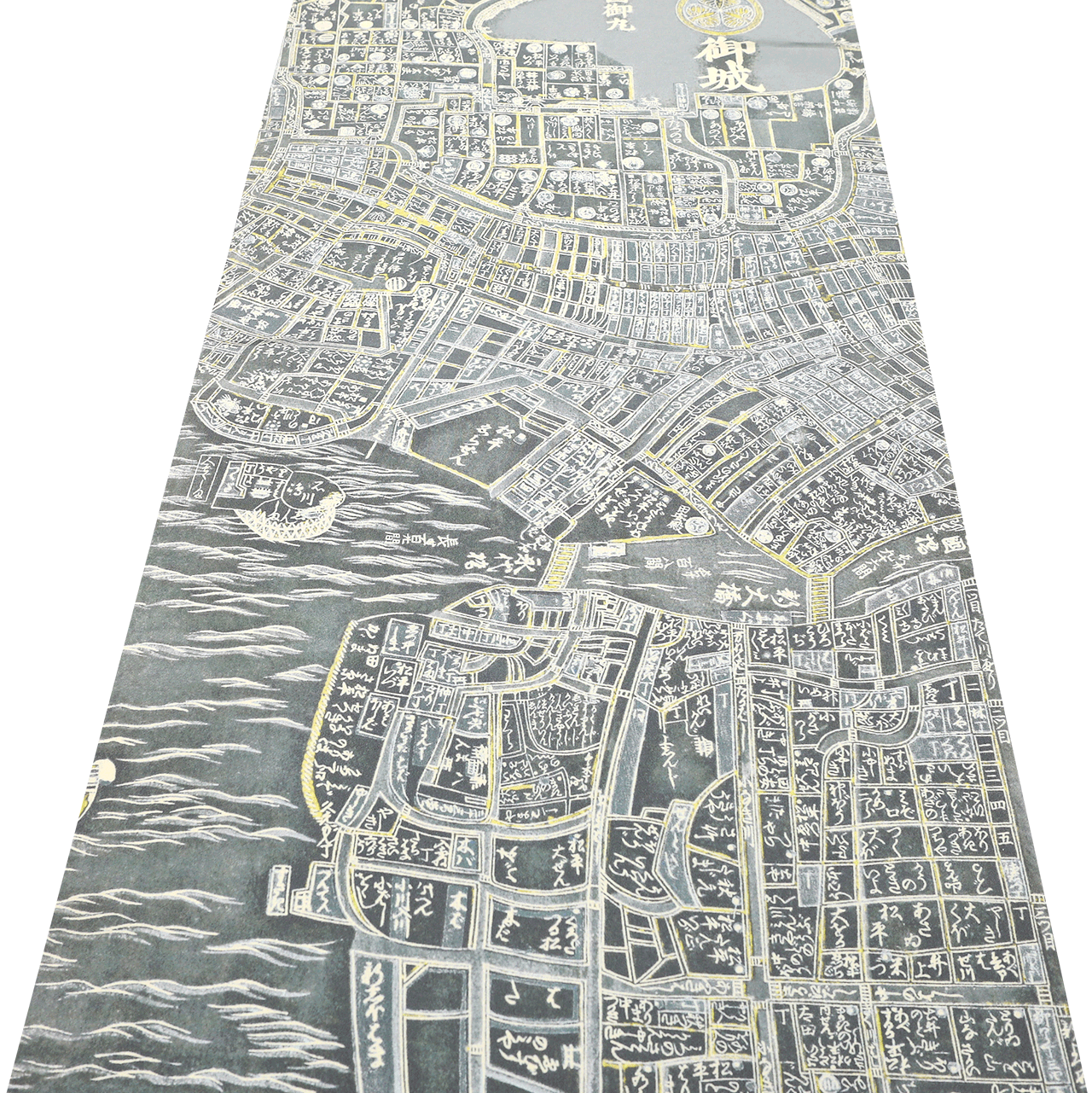

The cloth used for tax payments was made from choma (苧麻), a type of ramie plant known locally in Okinawa as bu. It belongs to the nettle family and is similar to hemp in its fiber quality. There were two main types of cloth used for tax. The first was jonofu, or tribute cloth, which was usually plain white. After it was woven, the fabric was bleached using seawater. The second was goyofu, or official-use cloth. For this, weavers had to carefully reproduce patterns based on design drawings called oezu (figure 1), which were sent from the royal court. In the Yaeyama Islands, weavers were often required to produce very fine kasuri fabrics, such as konshima hosojofu (navy kasuri) and akashima hosojofu (red kasuri).

Oezu (御絵図) pattern orders sent from the royal court.

Photo: SHIOKAWA, Yuya

In the head tax system, the weaving of ramie cloth was a duty assigned to women. The work involved everything from cultivating the ramie plant to preparing the thread and weaving, a process that took an enormous amount of time and effort. The required quantity and quality were strict, and it’s no exaggeration to say that women spent nearly all their time producing cloth for tax.

“But you know,” says Yoshiko Taira, “if you delivered a really well-made piece, you were rewarded with something called kuroumai, rice given to recognize your hard work. I think that helped keep people motivated, even under such harsh conditions.”

Taira, who serves as chair of the Ishigaki Island Textile Cooperative, guided us through the Yaeyama Museum in Ishigaki. Standing in front of a historical oezu from the museum’s collection, she leaned in to study it closely. Beside her stood fellow board member Kumi Shimura, also examining the design with focused attention.

Both are highly skilled weavers, and they are currently working on a project commissioned by Keita Motoji, second-generation of Ginza Motoji, to reproduce one of the kasuri patterns found in these old oezu. “We’ve been talking about this for years,” says Taira with a smile. “We always said, ‘These designs are so interesting. It would be fun to try making one.’”

Shimura nods and adds, “But I doubt the artists who drew these patterns gave any thought to the weavers. You can tell just by looking at them. If they had, there’s no way they would have come up with something this complicated.”

Even so, the two speak with respect and curiosity. The very difficulty of the patterns, they say, is what made them worth taking on, both then and now.

“Once you actually sit with an oezu, you realize how complicated and demanding these patterns really are. And when you start trying to turn them into actual design plans, it becomes even clearer. You find yourself wondering, how many threads are we going to have to tie off just to make this one motif?” They laugh a little, but their words carry weight. “We’ve been given a great opportunity,” they say. “But of all the designs to choose, of course we went with one of the hardest.”

The museum stands on the former site of the kuramoto, the government storehouse that once enforced the head tax. Just outside the entrance, a monument marks 100 years since the tax’s abolition, built in 2003. One can imagine all the stories, both sorrowful and joyful, that played out in this place. “Compared to people back then, we have it so much easier. We have tools, resources, everything. There’s no excuse not to try. We need to face these challenges while honouring the people who came before us,” says Taira, as both women share a quiet smile.

The History of Yaeyama Joufu

The exact origins of Yaeyama Joufu are unclear. However, a historical Korean record known as the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty notes that in 1477, a Korean shipwrecked on Yonaguni Island witnessed weaving with ramie. This suggests that by at least the late 15th century, textiles made from ramie were being produced in the region.

In the early modern period, Yaeyama Joufu developed under strict oversight as a form of tax cloth, as mentioned earlier. Within these harsh conditions, the craft became more refined, and weaving techniques reached a high level of sophistication.

Then came the Meiji era. After the dissolution of the Ryukyu Kingdom and its transition into Okinawa Prefecture, the head tax was finally abolished in 1903. Around that time, a new technique called nassen was introduced.

Keiko Taira, who often speaks publicly in her role as chair of the textile cooperative, explains it clearly.

“At the time, various new industries began to emerge in Ishigaki. The royal government’s control faded, and the pressure of the head tax began to ease. Even the Sho family, who had ruled the Ryukyu Kingdom, started running shops to survive. As Yaeyama Joufu shifted from tax cloth to a cash crop, new looms were invented for weaving finer kasuri patterns. That’s actually the origin of the Yaeyama-style upright loom we still use today.”

Around the same period, machine-spun ramie yarn began flowing into Yaeyama in large quantities. Compared to the hand-spun threads used previously, this yarn was straighter, smoother, and had no joins, allowing for much faster weaving.

“Yaeyama also had access to a great natural dye called kuuru(see fig. 2),” she adds. “Since we had this dye, someone must have thought, ‘Why not try using it?’ That’s probably how nassen, got its start here (fig. 3).”

Kuru (紅露)

About Kuuru

The distinctive dye used in Yaeyama Joufu is called kuuru. It comes from a species of yam that grows wild in the forests of Ishigaki and Iriomote Islands, with some plants reaching up to 70 to 80 centimeters in size. The weavers themselves venture into the mountains to harvest kuuru, digging out the roots with large shovels. When these black, oddly shaped roots, resembling giant taro, are cut open with a hatchet, the inside reveals a vivid red color. The liquid that oozes out is so deep in hue that it resembles blood.

Kuuru sap is highly astringent and can cause skin irritation if it touches the skin. The older the root, the deeper its red-brown color, making it ideal for use as dye; younger roots tend to have a lighter, more orange color and produce a paler dye.

To prepare the dye, the roots are grated with a large grater, wrapped in gauze, and squeezed to extract the juice. This juice is then left to sun-dry naturally until it is reduced to about half its original volume, creating a concentrated dye liquid.

Photo: SHIOKAWA, Yuya

Nassen Dyeing

Photo: SHIOKAWA, Yuya

As a result, Yaeyama Joufu gradually adopted a structure where machine-spun yarn was used for the warp, while traditional hand-spun yarn continued to be used for the weft.

The nassen process also evolved. One key innovation was a tool unique to Yaeyama Joufu called the ayagashira (fig. 4), developed specifically for stencil dyeing warp threads.

In this method, the warp threads are wound onto a wooden frame and brushed with a concentrated extract of kuru. Compared to the older process of hand-tying threads and soaking them in dye, this approach greatly improved efficiency. Once dyed, the warp could be transferred directly onto the Yaeyama-style upright loom and woven without additional preparation. The ayagashira functioned both as a dyeing tool and as part of the loom setup itself, making it a truly innovative development.

Ayagashira (綾頭)

Photo: SHIOKAWA, Yuya

"Nassen joufu has to be seawater bleached," says Taira. That’s because the kuuru dye paste won’t fully bond to the fibers unless the finished cloth is first dried in the sun, then soaked in the seawater. What’s fascinating is how a traditional process became essential to a new technique. From that point on, nassen joufu became the mainstream form of Yaeyama Joufu, and the craft grew into a key industry for the islands.

The Future of Yaeyama Joufu

We leave the museum and head to the weaving cooperative. The three-story concrete building in Ishigaki City incorporates traditional Okinawan elements in its design, such as red roof tiles and Ryukyu limestone. On the first floor are the weaving and dyeing rooms, a classroom, and a space for inspecting finished bolts of fabric. The second floor houses an archive and a shop open to the public. On the spacious third floor, where you can see the sea in the distance, kasuri tying is done.

The Yaeyama Joufu cloth that Taira and Shimura are currently working on is a hand-tied kasuri piece based on a historical oezu design, a technique from before nassen dyeing was introduced. Taira explains that, in the cooperative’s training program, this is one of the final skills students learn. Beginners start by weaving nassen bolts, then gradually progress to hand-tied kasuri depending on how many bolts they’ve completed. There, they learn how to dye thread using natural dyes like indigo and fukugi, and eventually become able to weave both obi and kimono fabric. Students also learn to weave Yaeyama minsa, a cotton textile often used for men and womens summer obi. Every course requires mastering the entire production process from start to finish. Only after understanding and internalizing each step can they move on to the next. This commitment to complete hands-on learning forms the foundation of Yaeyama Joufu. “Then, for the parts that need teamwork, we do it together,” says Taira.

The building is alive with activity. “The timing today is perfect,” Taira says brightly. In the dyeing area, kuuru is simmering over a flame while strips of fukugi bark are spread out on a sheet nearby. Traditionally planted as a windbreak around homes, fukugi is also known for producing Ryukyu’s iconic yellow dye and is used in Yaeyama Joufu. But rising costs associated with harvesting it have made it harder to obtain.

“The same goes for kuuru,” adds Toshie Urasaki, a veteran weaver from Iriomote Island and an expert forager of local plants. This member of the yam family grows naturally in the mountains of Ishigaki and Iriomote, you locate it by spotting its vines. While cooperative members harvest only what they need, some commercial collectors overharvest, creating serious concerns. “It’s getting harder to find in the easy-to-access places. We have to go deeper and deeper into the mountains. We go fully geared up with pickaxes, rubber boots, everything,” she says with a laugh.

The choma used for the weft, is cultivated by the cooperative in shared fields. There are said to be more than 60 types of choma across Asia, but Yaeyama Joufu uses a variety called shiro-bu (White choma). The threads are spectacularly white, and almost look like silk. They take coloured dyed beautifully. The best thread comes from plants about 40 to 45 days old, when the fibers are straight and easy to strip into clean threads. Urasaki is also an expert in choma processing. She and Shimura regularly lead hands-on workshops to teach the traditional hand-spinning technique.

Taira says these workshops have been a priority for the cooperative. “Each class has about fifteen students, but only a few will continue making after graduation. Still, just increasing the number of people who know how to spin ramie is valuable in itself.” Not long ago, it was normal to see grandmothers making choma thread in their homes and to hear the clatter of looms across the island. These once-familiar sights and sounds have almost vanished over the past fifty years, and now they’re being revived. “We’re trying to first increase the number of people who’ve seen or touched choma, even just once,” she says. “It’s been eleven years since I became chair. I’ve kept inviting anyone who shows interest, and recently, it feels like the effort is finally paying off.” This year, there are even four male students which to me is a sign that the craft is no longer just women’s work. “You can really feel the times are changing.”

Inside the weaving room, everyone is focused on their work. The Yaeyama-style looms are compact and specially designed to prevent the warp kasuri thread from slipping out of alignment. On the loom of a student weaving their very first nassen bolt. While there are many ways to create kasuri, this particular method, introduced in the Meiji period, became especially popular not only because it made the process easier, but because it allowed dyed threads to be set directly onto the loom with minimal prep. Still, watching the actual process, it’s clear this isn’t simple work. Using a bamboo brush to apply the thickened kuuru dye takes skill and precision. And there are some kasuri patterns that can only be expressed through nassen. Kiyomi Motomiya, a weaver of 23 years, smiles and says, “I really like stencil-dyed joufu.”

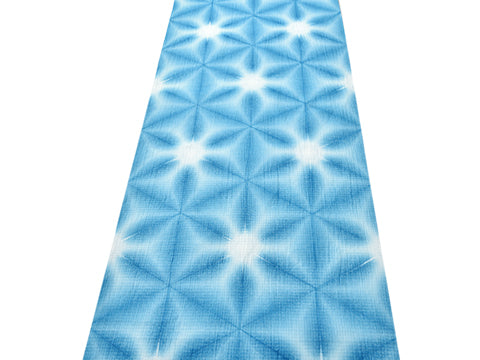

At another loom facing the hallway, Shimura works with a serious expression. She’s battling with the complex hand-tied kasuri design based on an oezu. Since it’s pre-nassen, her loom doesn’t have the ayagashira. Still, both techniques, nassen and hand-tied kasuri, use a traditional Ryukyu weaving method called teyui, where the kasuri threads are tied at regular intervals and then slightly shifted left and right as the weft is woven in to form the design. Abstract patterns like bima (currents) and busa (stars) are subtly altered by the weaver’s technique and sense of rhythm, creating a rich, expressive finish.

Because the pattern she’s reviving is so detailed, Shimura is adjusting the placement and spacing of the kasuri threads with great care as she begins to weave. At one point she murmurs, “I’ll need to talk with them, this one and that one have a bit too much space between them, so maybe I’ll move them a little.” By “them,” she means the kasuri patterns themselves, speaking as if she’s in conversation with them. In fact, everyone involved with Yaeyama Joufu speaks of the materials with a sense of respect and affection. Life is drawn from the island’s nature, transformed into thread, dyed, and woven. That’s why the plants, the thread, and even the patterns themselves are treated almost like living beings something to be listened to and worked with.

The cooperative, founded in 1976, will soon mark its 50th anniversary. It now has 58 members. While challenges remain, generational shifts, skill transmission, securing materials, the spirit is forward-looking, and committed successors are emerging. “I think our cooperative is slowly starting to see a path forward,” says Taira. “Even someone who starts with minsa can move up to weaving joufu if they keep training."

Efforts are also underway to ensure the future of kasuri and thread-making. Taira, who just finished dyeing the kasuri threads for the oezu revival, reflects, “We need to prove that these classical patterns can still be made. We also need to show younger generations that the cloth they’re weaving now is great, but the cloth of the past is just as amazing. Let’s look at both.” She wants to give students more opportunities to view oezu, and to revive hand-spun warp threads, which fell out of use with the rise of machine-spun ramie. “The foundation is there,” she says, her voice full of conviction. By moving forward with both tradition and modern techniques, Yaeyama Joufu is drawing a new future.

The upcoming Yaeyama Joufu exhibition at Ginza Motoji will feature new bolts and obi alongside a special piece: a hand-tied kasuri kimono bolt based on an original oezu. This collaboration between the cooperative and Ginza Motoji has been years in the making, starting even before the pandemic, and now it’s finally coming to life. The spirit of Ishigaki - its nature, history, and people is all woven into the cloth, bringing the feeling of summer from the islands to Ginza.

TAIRA, Keiko - Chair of the Ishigaki Island Textile Cooperative

TAIRA, Keiko - Chair of the Ishigaki Island Textile Cooperative

Photo: SHIOKAWA, Yuya

*Note 1

Traditionally, kasuri threads are made by tightly binding sections of the yarn to prevent dye from penetrating certain areas. When the threads are dyed and the bindings are removed, the undyed portions create the distinctive kasuri pattern. In Yaeyama, however, a different approach is used. Instead of binding, the dye is directly applied to the threads before weaving — a method known as nassen. In Yaeyama Joufu, this technique is uniquely adapted for kasuri production: using a bamboo brush, artisans carefully rub kuuru, a natural dye, into the threads by hand. This distinctive method sets Yaeyama Joufu apart from other kasuri textiles.

Yaeyama Joufu - May Exhibition

Event Information

Dates: Friday, May 23 – Sunday, May 25, 2025

Gallery Talk (Japanese only)

Date & Time: Saturday, May 24, 10:00–11:00

Speaker: TAIRA, Yoshiko (Chair, Ishigaki Island Textile Cooperative)

Venue: Ginza Motoji

Capacity: 40 guests (Free / Reservation required)

Work Commentary Session (Japanese only)

Date & Time: Sunday, May 25, 14:00–14:30

Venue: Ginza Motoji

Capacity: 10 guests (Free / Reservation required)

Artist in Attendance

Taira-san will be present at the store during the following times:

-

Friday, May 23: 15:30–18:30

-

Saturday, May 24: 11:00–18:30

-

Sunday, May 25: 11:00–18:30

名古屋帯

名古屋帯

袋帯

袋帯

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

浴衣・半巾帯

浴衣・半巾帯

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

肌着

肌着

小物

小物

履物

履物

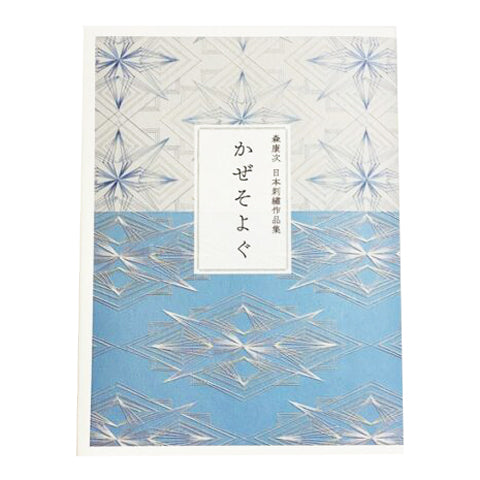

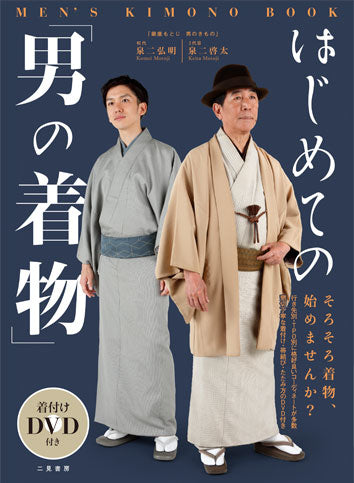

書籍

書籍

長襦袢

長襦袢

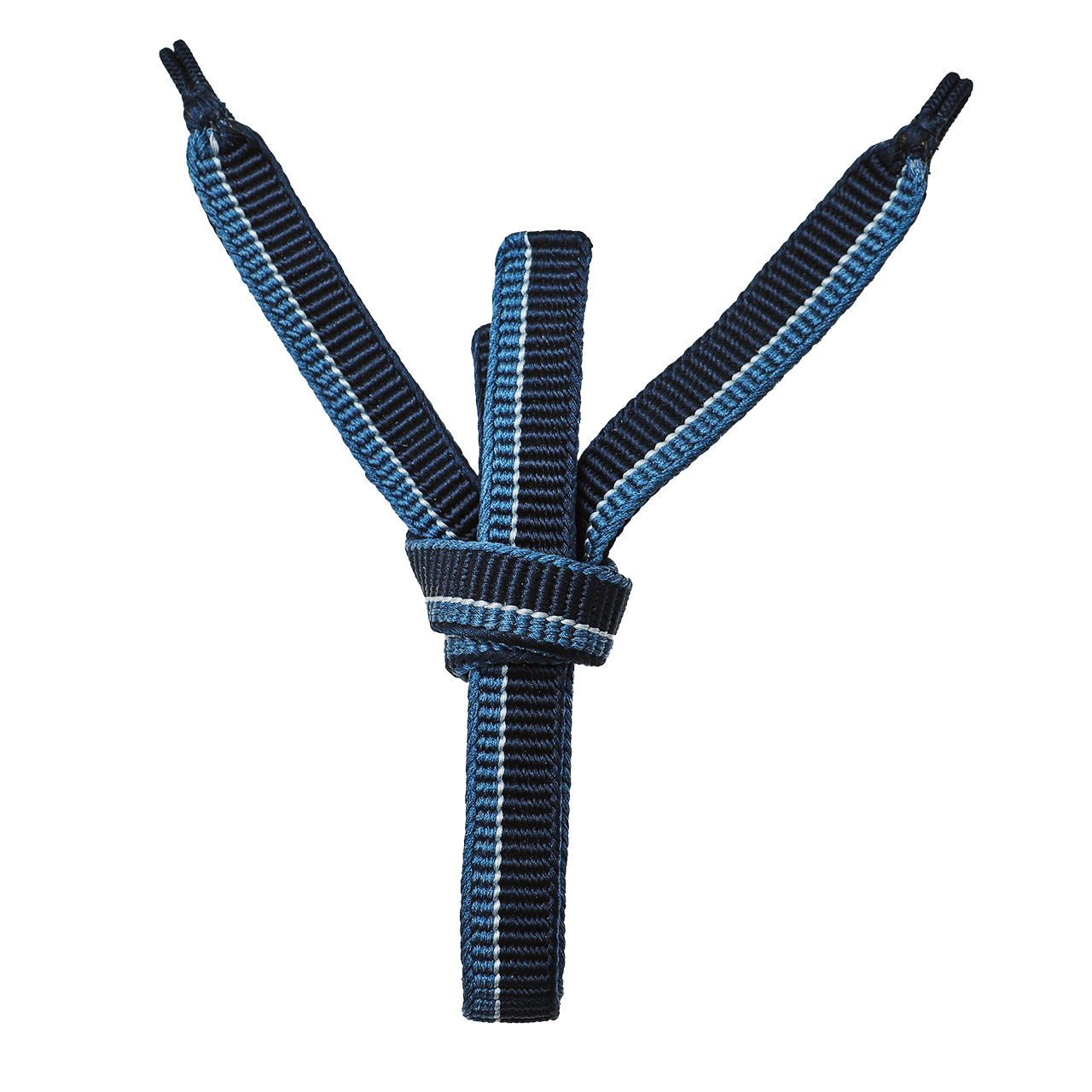

小物

小物

帯

帯

お召

お召

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

袴

袴

長襦袢

長襦袢

浴衣

浴衣

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

額裏

額裏

肌着

肌着

履物

履物

紋付

紋付

書籍

書籍