*This text is from 2018, and was originally written in Japanese

A soft, refined, and yet brilliantly vivid pink.

The safflower-dyed textiles of Koichi Yamagishi have captivated kimono and textile lovers alike.

“When I wear Yamagishi-san’s kimono, I feel a surge of strength from deep within.”

Each bolt of fabric is gently and carefully crafted, respecting the natural qualities of the materials, his fabrics warmly envelop the wearer and imparts a sense of vitality.

The fact that many customers have not just one, but two or three kimono by him is a testament to the powerful presence his work carries.

In mid-July 2018, we visited Yamagishi-san’s studio, the Akakuzure Natural Dye Research Institute, located in Akakuzure, Yonezawa City, Yamagata Prefecture, for a two-day, one-night trip.

During those two days, temperatures in Akakuzure reached 35°C. Simply standing still we were drenched with sweat, but Yamagishi-san welcomed us with a refreshing smile that seemed to sweep away the intense heat.

Choosing to live in harmony with the flow of nature, Yamagishi-san’s smile radiates a deep gratitude and affection for all living things.

In a modern world overflowing with conveniences and instant gratification, witnessing his work made us reflect on what true richness really means.

Making of Benibana-Mochi

Yamagishi-san’s original technique, Benibana Kanzome, is a method of safflower dyeing performed in the harsh winter cold of Akakuzure.

This time, we had the opportunity to observe and experience the making of beni-mochi (safflower cakes), which is done in the summer in preparation for the winter dyeing.

The history of safflower cultivation in Yamagata Prefecture is long, said to date back about 400 years to the late medieval period.

Safflower seeds are sown around April, and the flowers bloom in early July.

From hereon, we will refer to safflower as benibana.

AM 5:00

At Yamagishi-san’s workshop, the day begins at 4 a.m. with a trip to the benibana fields.

For about one month in July, during the blooming season, benibana are harvested early in the morning while the thorns are softened by the morning dew.

The best time to pick them is when the flowers are in full bloom.

The key is to gently twist and pull the petals free with your fingertips.

AM 6:50

After picking benibana, your hands become stained, as shown in the photo, and you may feel a slight tingling or itchiness.

This reaction is due to the power of the benibana, which stimulate circulation through contact.

It is a moment that makes you keenly aware that you are receiving the life of nature in the act of creation.

AM 7:00

Once the flower picking is complete, the next step is washing the petals.

The harvested petals are placed into baskets, which are then carried to the river flowing beside the workshop.

Yamagishi-san chose Akakuzure for his workshop specifically for its proximity to this pure water, near the source of the Mogami River. To him, the river is the lifeblood of the entire process.

Submerging the baskets in the river and vigorously washing the petals, the yellow pigment is washed away.

AM8:30

After the petals are washed, the excess water is carefully wrung out, and the petals are transferred into a big tub.

Yamagishi-sensei steps into the tub, lightly sprinkling water over the petals and then begins to tread on them. This process is called hanafumi.

Suprisingly the petals in the tub still retain much of their yellow pigment at this stage.

Note: Normally, Yamagishi-san performs this step barefoot, but since we were allowed to experience it ourselves this time, he kindly arranged for us to cover our shoes with plastic bags before stepping into the tub.

AM9:30

After about thirty minutes of constant treading, it becomes a lot smoother.AM9:40

AM10:00

During this process, a fine mist of water is occasionally sprayed over them, and the petals are turned and gently kneaded in a step called hanamushi (flower steaming).

By repeating this process thoroughly, the petals are fermented.

AM14:00

Just like making traditional mochi rice cakes, as the mixture becomes more viscous, it requires considerable strength to lift the pestle.

AM14:30

Taking an amount about the size of a large grape into your hand, you round it out, then press it firmly between both palms to squeeze out the moisture.

When it flattens into a thin, cracker-like shape, it is placed on a basket and left to dry in the shade for several days.

This becomes beni-mochi (safflower cakes), the dye that breathes life into the colors of Yamagishi-san’s Benibana Kanzome works.

The finished beni-mochi are carefully stored in jars inside the workshop, where they are left to rest until the kanzome cold dyeing season arrives.

Yamagishi-san originally worked in his family’s weaving business.

One day, while working at their factory in the center of Yonezawa City, where machine weaving was the norm, he decided to try hand weaving, and he was deeply moved by the superior texture it produced.

"Once you experience something truly good," he said, "there’s no going back."

Living among the grey skyscrapers of the city, it is easy to forget the simple blessings of nature. We are greatful of Yamagishi-san dedication and how he gently reminded us of these essential gifts.

In the quiet land of Akakuzure, Yonezawa City, Koichi Yamagishi continues to devote himself to the profound world of benibana dyeing.

Cherishing the sun, the water, and the wind, and creating his works with deep gratitude for the bounty of nature, he gave us a sense of renewal and, once again this year, a pure and vital energy.

Take a look at our current collection of Yamagishi-senseis work in our online store

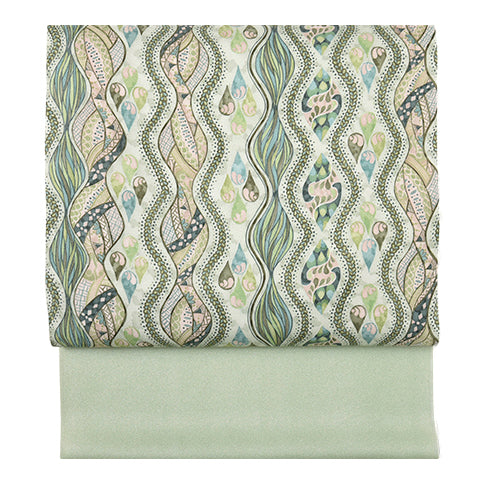

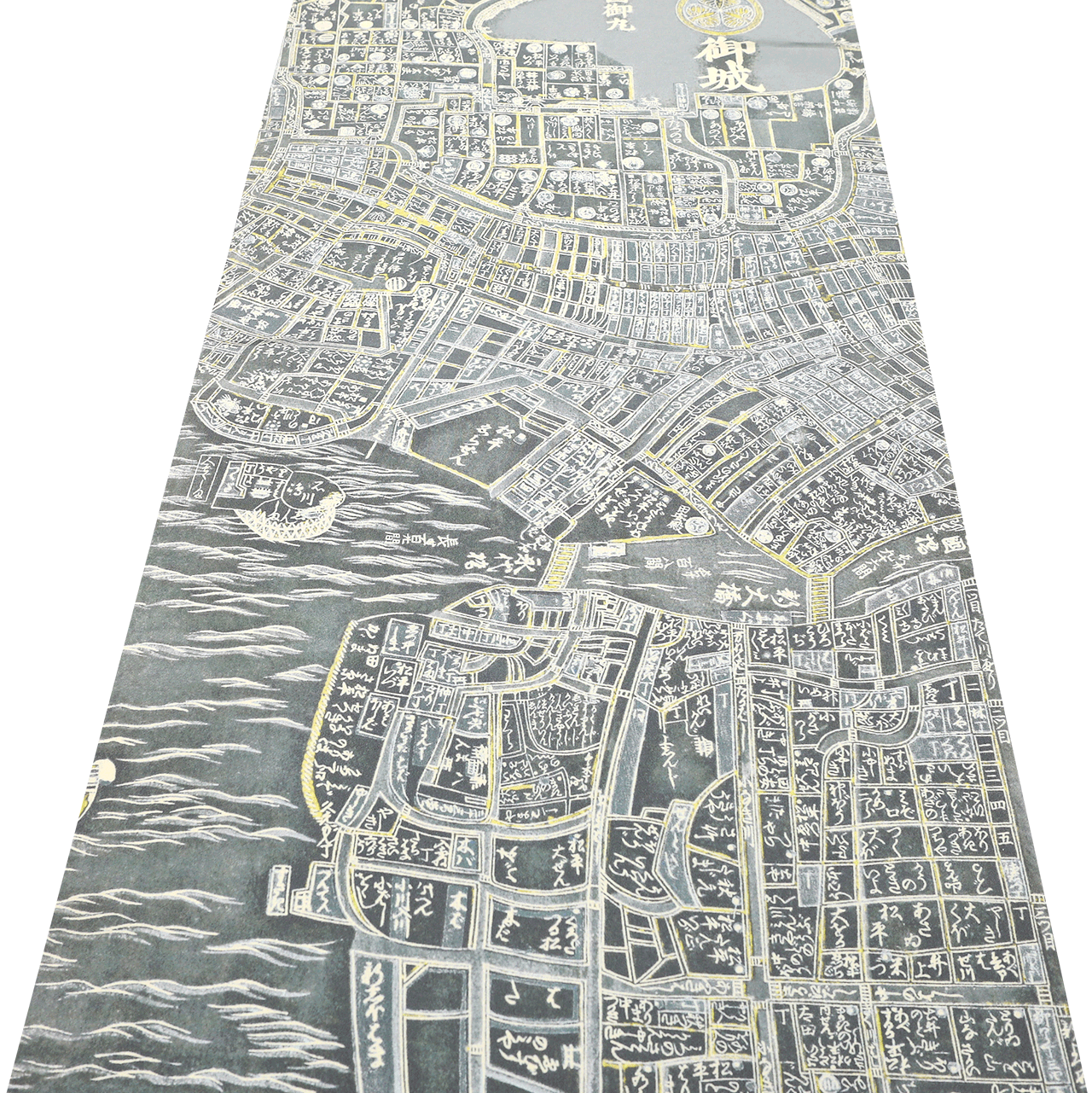

名古屋帯

名古屋帯

袋帯

袋帯

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

浴衣・半巾帯

浴衣・半巾帯

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

肌着

肌着

小物

小物

履物

履物

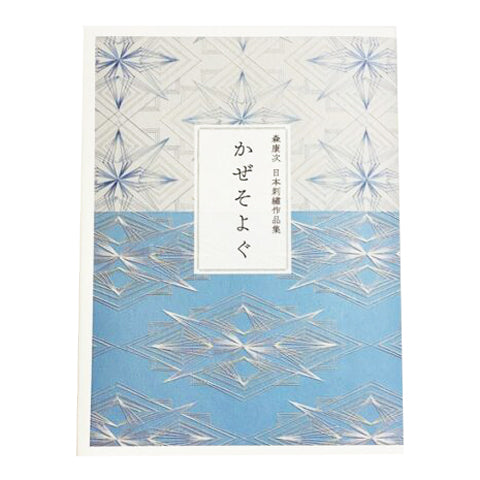

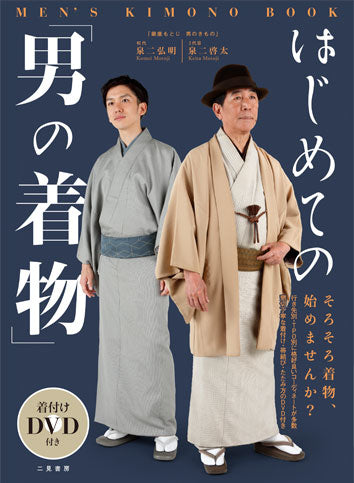

書籍

書籍

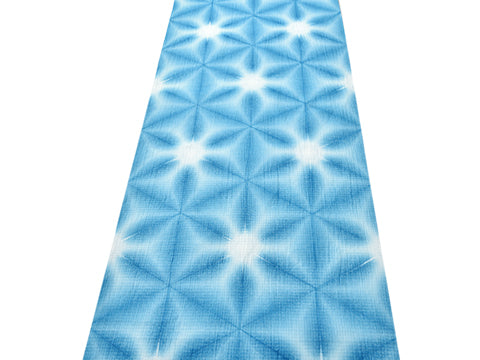

長襦袢

長襦袢

小物

小物

帯

帯

お召

お召

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

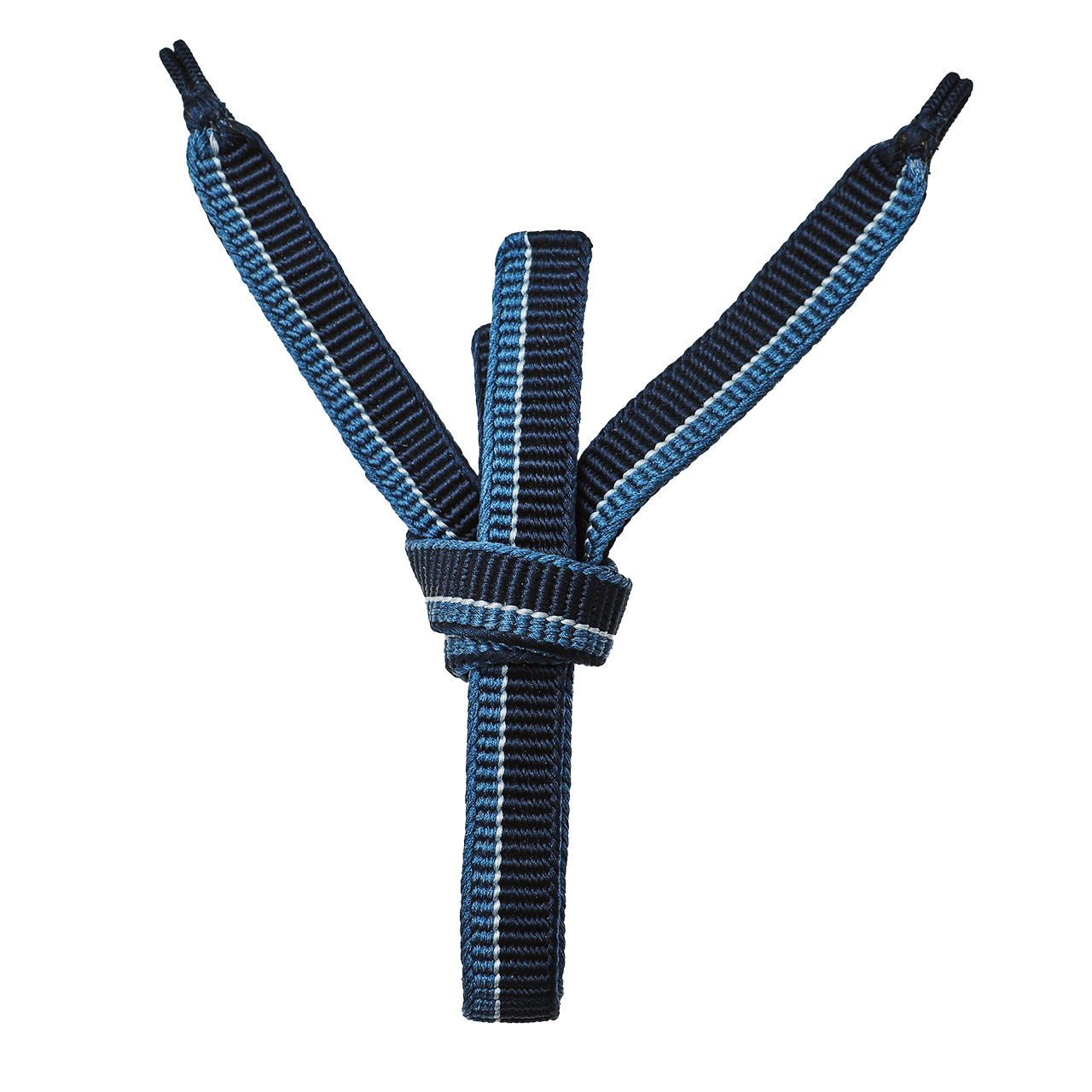

袴

袴

長襦袢

長襦袢

浴衣

浴衣

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

額裏

額裏

肌着

肌着

履物

履物

紋付

紋付

書籍

書籍