Japonism, became popular in Europe and the United States from the late 19th century to the early 20th century. The craze began with the display of items collected by Sir Rutherford Alcock, the British envoy to Japan, at the Second London World's Fair in 1862. A wide range of Japanese items, including ukiyo-e prints, kimono and katagami (Paper stencils used for dyeing), lacquerware, Buddhist statues, and ceramics, were introduced and served as a source of inspiration for many Western designers, artists, architects, and craftsmen. Suprisingly it was the paper katagami more so than the kimono or other textiles which had a bigger impact on craftspeople and commoners alike.

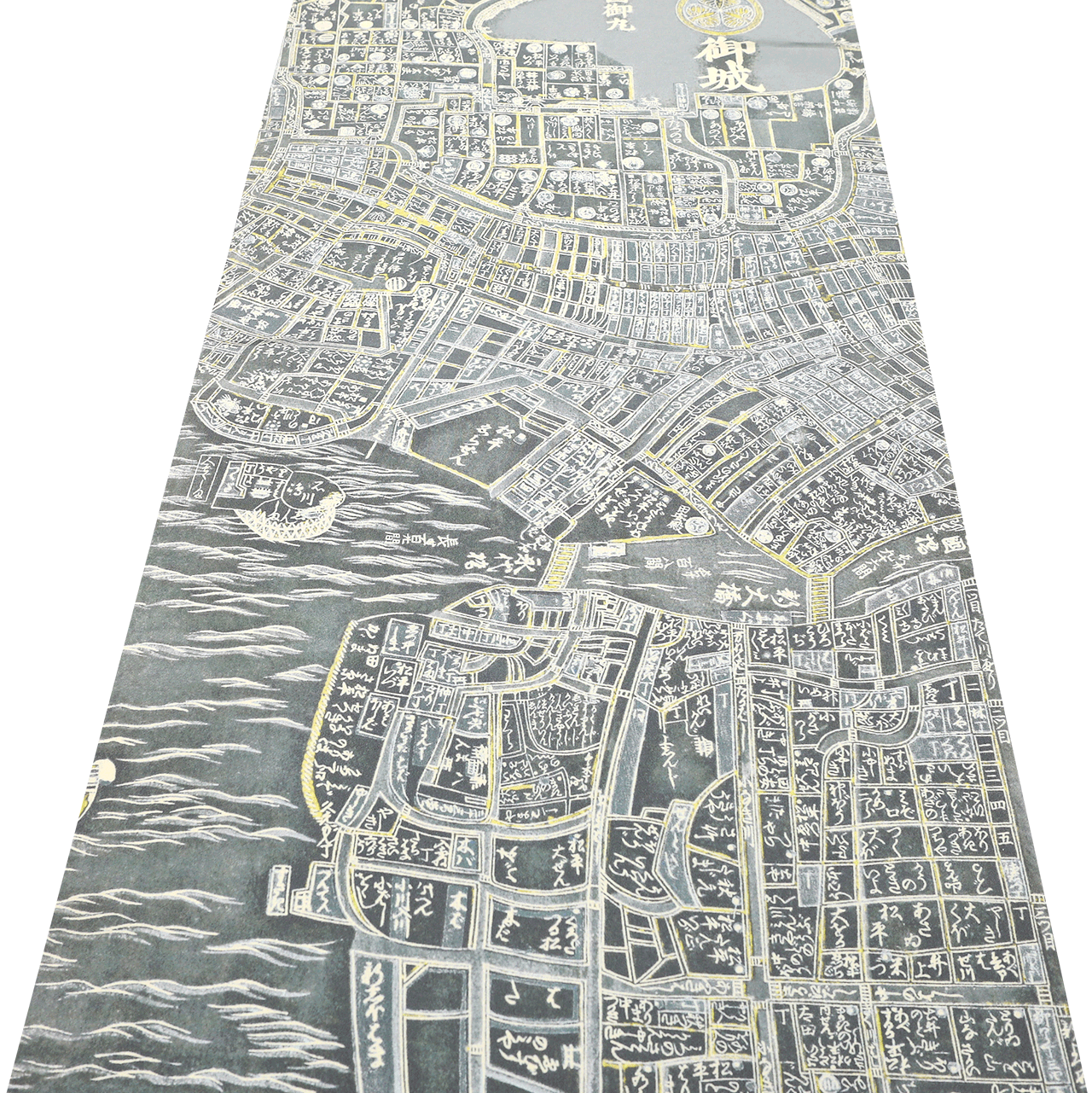

The word Katagami comes from two Japanese characters, 型紙, literally meaning paper stencil. These small stencils were usually made with Japanese washi paper, and then cut by hand to create the desired shape. They were often dyed with extract of persimmon, to make them more robust. This turned them their signature dark amber shade. Katagami are used in various resist dyeing techniques like Edo komon. chu-gata, kata-yuzen, and beni-gata-zome to create delicate and intricate patterns.

How did these paper stencils make their way from Japan through the western world, and how were they used and regarded in each country?

In Europe and the United States, these Japanese pattern templates were perceived as novel and exotic. They served as a fresh source of inspiration for Western designers and artists who were looking to break away from traditional Western aesthetics. The intricate and delicate patterns found in these templates influenced the development of new decorative styles in Western art and design.

Overall, Japanese pattern templates, like other Japanese art forms, played a significant role in the development of Japonism. They contributed to the blending of Japanese and Western artistic influences during this period.

『Stencil with Theme from Matsukaze』(Metropolitan Museum)

In recent years, it has become clear that a large number of Katagami from Japan are stored in various museums in Europe and the United States. According to Professor Yoko Takagi of Bunka Gakuen University, the numbers are staggering, with approximately 1,500 patterns in the Decorative Arts Museum in Paris, 4,000 in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, 10,000 in the National Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna, and 16,000 in the Dresden Museum of Decorative Arts, among countless others.

Despite the vast quantity of these patterns making their way across the world for nearly 2 centuries, they haven't received much attention until recently. This lack of attention can be attributed to the fact that, for Japanese people, these katagami were not pieces of art themselves, merely tools to create something bigger.

According to Professor Takagi, many katagami can be found in various textile dyeing workshops, and are often considered semi-disposable. Consequently, the awareness of these katagami as collectible items or subjects for museum exhibitions was low.

Katagami(Metropolitan Museum)

The exact history of how and why Japanese katagami have flowed in such large quantities overseas remains unclear. There is a lack of records and documentation about their export, leaving many aspects of this history shrouded in mystery. Though their journey is unclear, they began to gain significant attention from the 1880s. The patterns depicted, and the actual katagami themselves were adapted and used slightly in each different location to meet various regional needs and preferences.

Let's take a closer look at how Japanese patterns were utilized in the United Kingdom, France, the United States, and Germany.

【England】Katagami influencing Industrial Design.

Pink and Rose - William Morris (Metropolitan Museum)

The first-ever World's Fair, the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, featured the Crystal Palace as its centerpiece. The Crystal Palace, constructed using cutting-edge technology of the time with glass and iron, generated significant attention and became a major talking point.

World Fair -1851(Crystal Palace)

Despite this, the inadequacy of British design in comparison to other competing countries became apparent. This was addressed in the year following the exhibition when the Victoria and Albert Museum was established. The museum was to focusi on the aesthetic education of craftspeople as well as the general public, aiming to foster decorative and industrial arts within Great Britain. It was the exhibits from Japan that greatly inspired many British architects and designers.

As mentioned earlier, the introduction of Japanese craftsmanship and everyday items during the second London International Exhibition in 1862 served as a catalyst, gradually spreading Japonism. People began to favor a lifestyle surrounded by furnishings that incorporated the tasteful Japanese design.

The attention towards katagami specifically began to grow in the 1880s. In 1882, the craft designer Christopher Dresser introduced katagami in his publications for the first time. This spread japonism not only within the upper class, but down through the social strate due to an expension in DIY interior design. People started to refer to magazines, advertisements, and guides to select tools that allowed them to decorate stylishly at a low cost. Interior decoration served as a platform for women, in particular, to express their aesthetic sense, and patterns were the perfect tools for this purpose. Only two years later in 1884, Liberty department store began selling patterned stencil for use in surface decoration.

Fireplace Surround』Thomas Jeckyll (The Art Institute of Chicago)

As katagami were originally designed to create flat repeat patterns, they were easily adaptable to various media such as machine-produced textiles and wallpapers. They became a valuable source of design inspiration that could combine affordability and aesthetics, meeting the demands of the general public. Additionally, cotton textile factories in places like Carlisle and Manchester collected Japanese katagami and used them as references to develop new patterns for textiles.

In this way, Japanese patterns served as a significant catalyst for the development of industrial arts in a stagnating Britain.

【America】Enjoyed by the Wealthy

Philadelphia International Exposition Main Pavilion (Tokyo National Museum)

The trend of Japonism in Western Europe also spread to the United States, where, like in Britain, it flourished primarily in interior design and various aspects of design. American artists and designers looked to Japanese art, including katagami, as well as examples from Asia, India, and the Islamic world to inspire new artistic endeavors.

The trend became particularly prominent following the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition, where the Japan Bazaar was held. Afterward, Japanese goods stores began to open in urban areas across the United States. From luxury items to affordable ones, Japanese products became readily available, and Katagami were used in the design of high-end everyday items for the affluent. Some households even collected katagami themselves, although the exact purpose of these collections remains unclear.

Katagami(Metropolitan Museum)

Furthermore, collectors played a significant role in promoting Japanese art, such as katagami, to a broader audience. Prominent collectors traveled extensively throughout Japan to acquire fine pieces. Today, many of these collected items have been donated to American art museums and institutions.

【France】Katagami served as a source of inspiration for Art Nouveau artists.

Druid Vase - René Lalique (The Art Institute of Chicago)

France, where Art Nouveau flourished, had a keen interest in Japanese culture, and it would not be an exaggeration to say that it was the country where Japonism was most widely and deeply embraced.

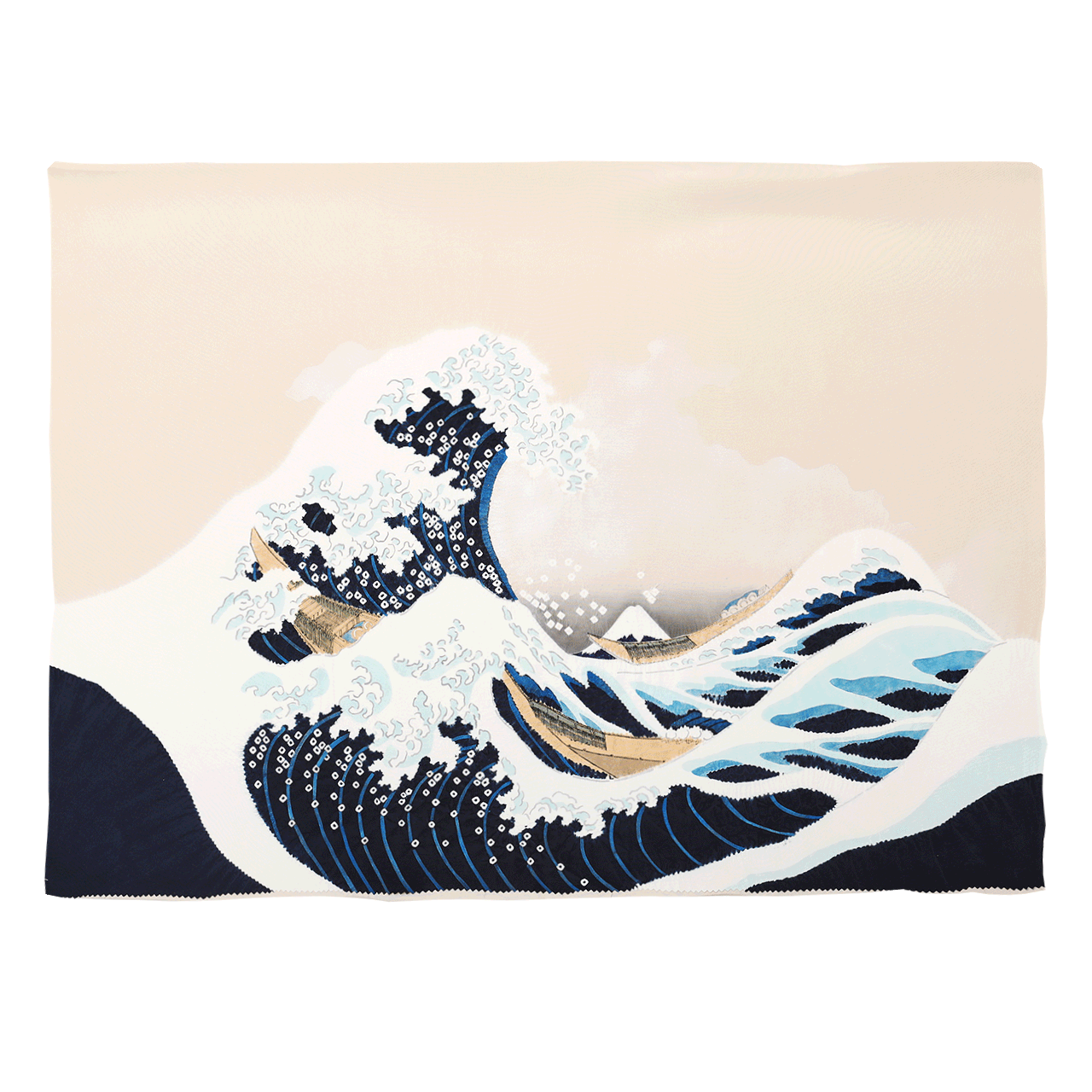

In various fields of decorative arts such as furniture, textiles, wallpaper, tableware, metalwork, and clothing, French designers collected Japanese craftsmanship for design inspiration. Among these collections, there were collections of katagami. While there are few specific examples that indicate which patterns were used in which designs, it is reported that the study of Japanese patterns was an important source of inspiration for jewelry designers of the Art Nouveau movement like René Lalique.

Laziness - Félix Vallotton(The Art Institute of Chicago)

Art historian Akiko Mabuchi has pointed out the characteristics of Japanese patterns, which include the use of subdued colors such as shibugami and white, and the reduction of natural motifs into simple designs arranged in a rhythmic composition. The simplicity and refinement of flat design, along with motifs inspired by nature's flora and fauna, made them easily adaptable to various forms of decoration. This, in turn, served as a catalyst for the rich achievements of the Art Nouveau and Art Deco movements.

Émile Gallé(Rijksmuseum)

【Germany】Katagami as Learning Materials

Germany, embraced Jugendstil, also known as Art Nouveau. In the latter half of the 19th century, Germany lagged significantly behind advanced countries like Britain and France in the fields of politics and economics. Especially, their domestic products had earned a reputation in the global market as "cheap and low-quality," making improvements imperative. As a solution, they established arts and crafts museums. These museums aimed to contribute to regional development, the training of craftsmen and industrial workers, and the enhancement of consumer tastes. Therefore, they collected and preserved "utilitarian" rather than merely "aesthetic" works of art and used them as teaching materials in affiliated arts and crafts schools. These collections even included katagami for various crafts.

Fragment(The Art Institute of Chicago)

Katagami were actively collected as examples when exploring new forms, and it is said that you can now find pattern collections throughout Germany. In addition, publications like the magazine "Geijutsu no Nihon" (Art of Japan), published in French, English, and German from 1887 to 1891, made significant contributions to the spread of patterns. These publications were not just meant for admiring as art pieces but were edited to serve as examples for people seeking new design principles that were in line with the times.

Yuko Ikeda of the Kyoto National Museum of Modern Art suggested that one of the reasons patterns were embraced in Germany was because, as Justus Brinckmann pointed out, "Patterns are fundamentally monochrome sketches, and from the simplification of means of expression, reliable stylization is created." Additionally, she speculated that patterns were valued in Germany due to the social conditions of the time, which aimed at promoting industry and improving the quality of people's daily goods. Patterns served as tools for mass production in this context.

Until now, katagami, such as those used in kimono and ukiyo-e prints, have received relatively little attention in Japan. However, these pattern templates have made significant contributions to the decorative arts in the western world. While there hasn't been extensive exploration of the advanced craftsmanship required to create these katagami or their connections to classical literature, the creative motifs carved into these templates have served as a new source of inspiration for the stagnant decorative arts in Western Europe.

During the Second London World's Fair, when the collection of Sir Rutherford Alcock, the British envoy to Japan, was displayed, the Japanese envoy to Europe at the time reportedly thought it looked like a collection of odds and ends. However, for Westerners of that era, these items were not only exotic but also served as a french source of visual inspiration due to their exceptional craftsmanship and creative patterns. Akiko Fukai, Honorary Curator of the Kyoto Costume Institute, has pointed out that the skills of Japanese craftsmen who produced such items and the wonder and respect for the extraordinary materials used were essential factors in the widespread popularity of Japonism, which went beyond being a mere fashion trend and penetrated into everyday life.

Beauty can be found in not just artwork itself, but also in the tools and everyday items used to create them. These tools have played a pivotal role in shaping major art trends worldwide. There may still be many undervalued aspects of Japanese culture that have not yet been fully appreciated, akin to the hidden treasures of Katagami.

[References]

- "KATAGAMI Paper and Japonism: Various Aspects of Technique and Image Pattern Propagation" by Yoko Takagi

- "KATAGAMI Style" by Nikkei Inc.

- "Japonism in Fashion: Kimonos Across the Sea" by Akiko Fukai (Heibonsha)

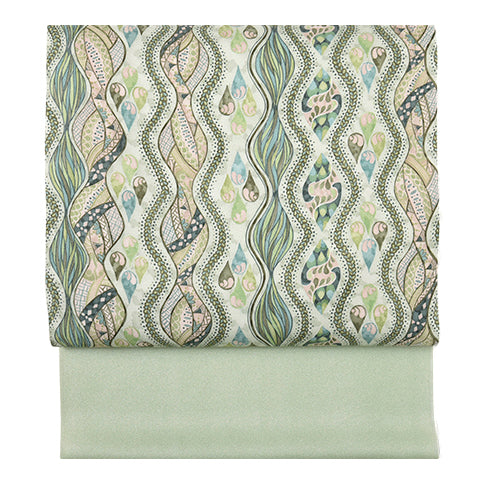

名古屋帯

名古屋帯

袋帯

袋帯

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

浴衣・半巾帯

浴衣・半巾帯

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

肌着

肌着

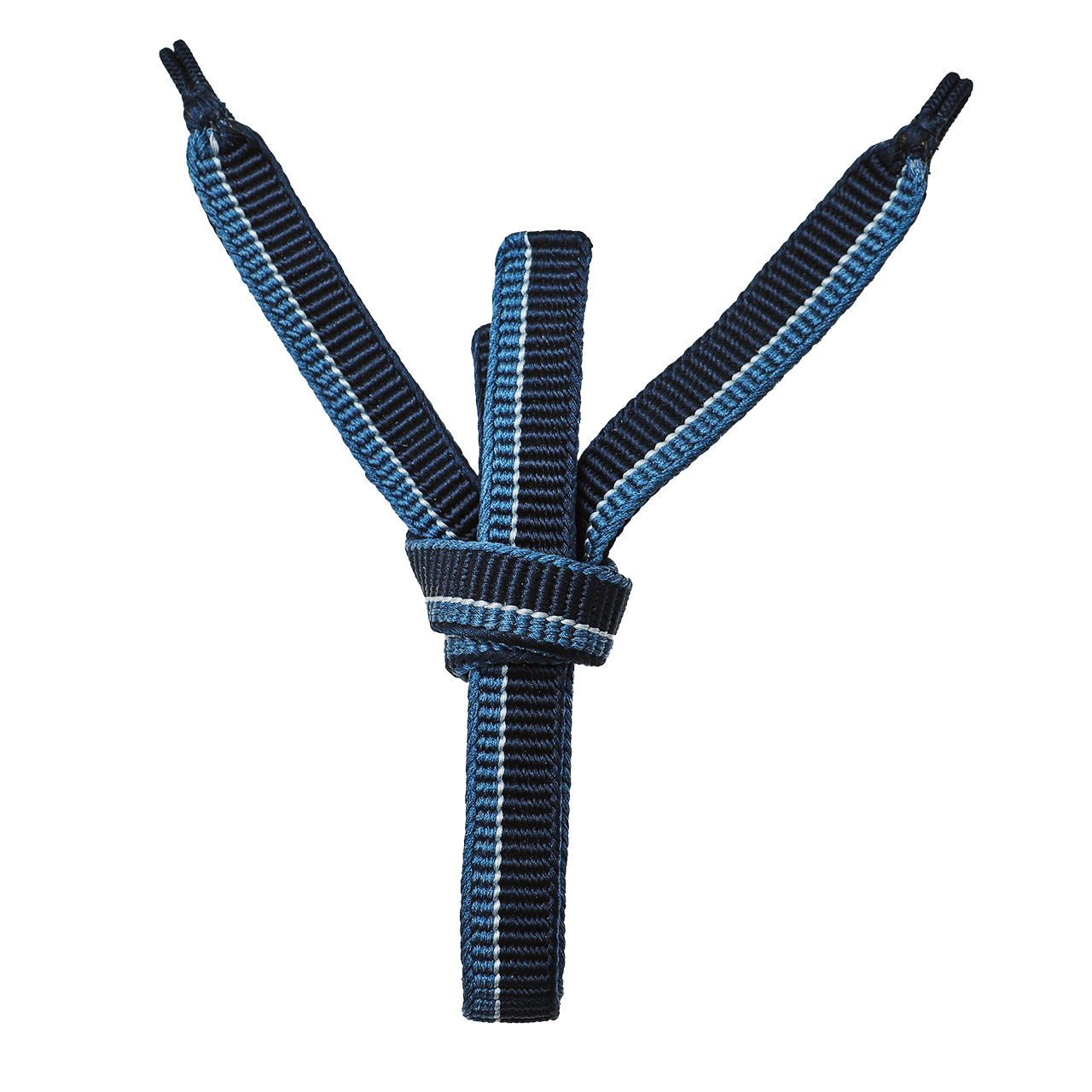

小物

小物

履物

履物

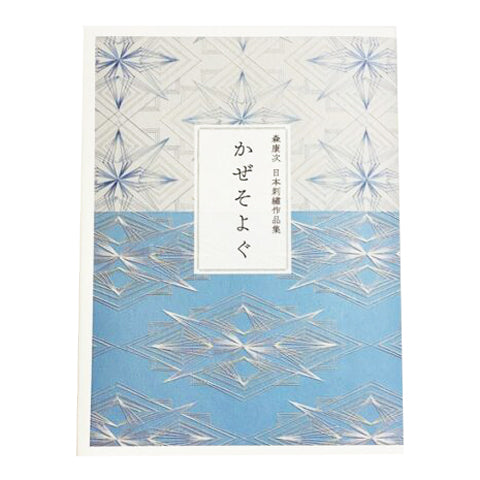

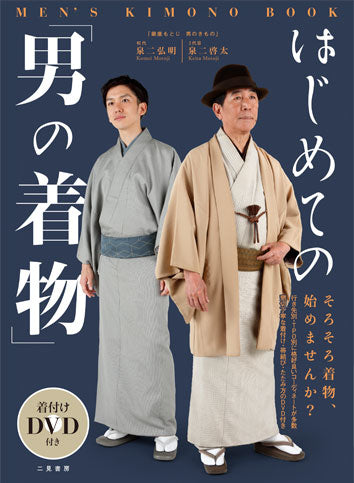

書籍

書籍

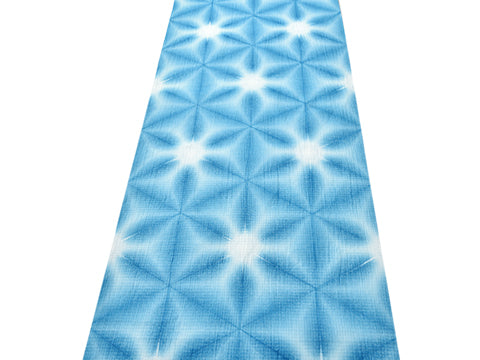

長襦袢

長襦袢

小物

小物

帯

帯

お召

お召

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

袴

袴

長襦袢

長襦袢

浴衣

浴衣

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

額裏

額裏

肌着

肌着

履物

履物

紋付

紋付

書籍

書籍