Crafting Nature: The Voice of Kuzu

In the mountain valleys of Shizuoka, not far from the Oigawa River, the rustling of leaves gives way to the quiet rhythm of a handloom. Inside a wooden workshop built in the early 1950s, kuzufu(葛布), a textile woven from the resilient kuzu vine, continues to be made by hand at the Oigawa Kuzufu workshop.

The workshop is led by Tatsuhiko Murai, together with his wife, their son, and a single apprentice. While the studio now focuses on kimono and obi, it originally specialised in wallpaper for export. Even so, kuzu has a much longer history in Japan, primarily as a wearable. For generations, it was worn as both everyday and ceremonial clothing, appreciated for its texture, breathability, and subtle lustre. Though rarely seen today, its role in the history of Japanese dress is deep and enduring.

When we arrived, the Murai family served green tea and sweets made with kuzu starch. The walls of the reception room were papered with kuzufu, giving the space a soft, organic light. Shelves were stacked to the brim with books on textiles from across Japan.

Revival

In the 1950s, Murai's father began working for a company that made fishing nets. Through this work, he learned to handle natural fibres and became familiar with the properties of kuzu. Before long, he set up his own workshop along the Oigawa River and began to specialise in kuzufu weaving.

In the early years, the workshop produced primarily interior textiles. Rolls of kuzufu wallpaper were supplied to stores in Ginza as well as overseas. The cloth’s irregular texture and organic quality suited the aesthetics of the time.

About twenty years ago, the focus shifted to wearables. For Murai, this was not so much a new direction as a return. Kuzu had long been worn in Japan, especially by common people. From the Nara to Edo periods, it was used for summer clothing, undergarments, and even as an inner layer beneath armour. Village records from the Edo period list kuzufu kimono among household belongings, reflecting its role as a practical, breathable fabric for daily life.

What is Kuzufu?

Kuzufu(葛布)is a textile made from the long, sinewy fibres of the kuzu(葛)vine, which grows wild across the Japanese countryside. At Oigawa Kuzufu, vines are gathered from the riverside of the Oigawa River, then slowly transformed into thread through a series of careful, hand-driven processes.

Outside of Japan, especially in the southeastern United States, kuzu is often seen as a nuisance. Sometimes called Japanese knotweed, it spread aggressively after being introduced in the 19th century, earning the nickname “the vine that ate the South.” In Japan, however, the plant coexists with its environment. Natural predators like kamemushi (stink bugs) and seasonal dormancy in winter help keep it in balance. It is not considered invasive.

Murai describes the workshop’s approach as one of listening. The vines are selected by hand, boiled, fermented in straw, and washed in the river. The fibres are prepared with nuka(糠), or rice bran, to keep them supple. They are then spun into thread by hand, dyed with materials gathered from the garden, and woven on looms that respond to the body.

Every step is done on-site. Nothing is outsourced. The scale is small, but each bolt of kuzufu carries the rhythm of the river, the shape of the seasons, and the attention of the people who made it.

Murai often says that kuzu is talkative. “In the fields,” he tells us, “there are vines that call out, 'Make me into kuzufu.'”

The Making Process

-

Harvesting

The kuzu vines are collected primarily from the riverside of the Oigawa River. Vines that are four to five metres in length, growing as straight as possible and not heavily tangled, are preferred. If the vine is twisted or knotted, the resulting threads are likely to tangle during processing. -

Boiling

Back at the workshop, the vines are boiled over gas or fire to loosen the fibres. -

Fermentation

The boiled vines are placed in a pile of straw outside the workshop, covered with a tarp. This muro(室)ferments for about three days in summer or up to a week in winter. It becomes almost hot to the touch. -

Fibre Extraction

After fermentation, the fibres are stripped from the vines using nuka, which softens and separates them. -

River Washing and Drying

The fibres are washed in the Oigawa River to remove any remaining residue. Once clean, they are sun-dried, then split and separated into threads. -

Spinning

The fibres are twisted into thread by hand. The quality of this step has a direct impact on the final weave. “You can’t become good at weaving unless you’re good at washing the threads,” Murai says. -

Dyeing

Only natural dyes are used, many of which are taken from their garden. Beni(紅), zakuro, biwa, and kurogane mochi, produce a wide range colours that shift gently over time. Traditionally, all threads were dyed in solid tones. The recent use of kasuri(絣)threads marks a new chapter, adding pattern and movement to the weave. -

Weaving

Weaving is done on looms old and new. Murai prefers the older wooden types that move with the weaver’s body. Newer looms with metal fastenings tend to be stiff and can tire the body.

Traditionally, kuzufu used cotton for the warp and kuzu for the weft. Murai has tested other warp materials including linen and silk, but only cotton and hand-reeled silk have produced cloth soft enough to be worn comfortably.

Each step depends on the one before it. There is no rushing. The fibre determines the pace.

Listening to the Fibre

At Oigawa Kuzufu, weaving is not just a skill but a way of listening. Some vines in the field seem to call out, asking to be made into cloth. Others remain silent. That same attention continues at every stage.

Apprentices begin not at the loom, but with the raw vine. Washing, stripping, and twisting the fibre teaches them how the material behaves. “You can’t become good at weaving unless you’re good at washing the threads,” Murai says. The knowledge is physical and learned through the hands.

Weaving is a solitary task; one artisan, one loom. The room is quiet but alive with the rhythm of fibre and thread. The weaver listens to the tension, the texture, the quiet voice of kuzu. The pace is set not by the clock, but by the material and the seasons.

This is not nostalgia. It is a way of working that endures; quietly, attentively, and fully present.

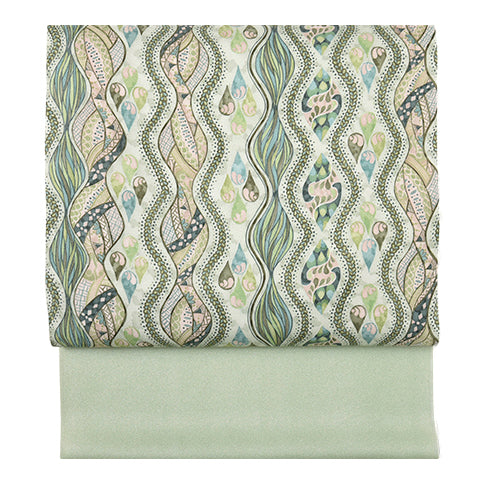

名古屋帯

名古屋帯

袋帯

袋帯

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

浴衣・半巾帯

浴衣・半巾帯

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

肌着

肌着

小物

小物

履物

履物

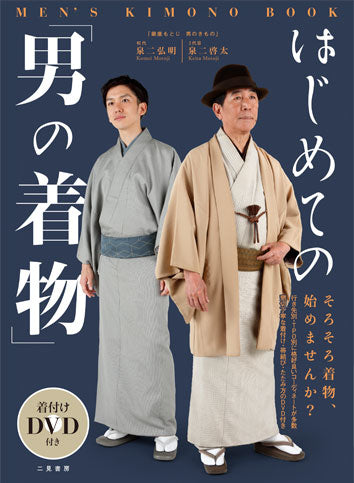

書籍

書籍

長襦袢

長襦袢

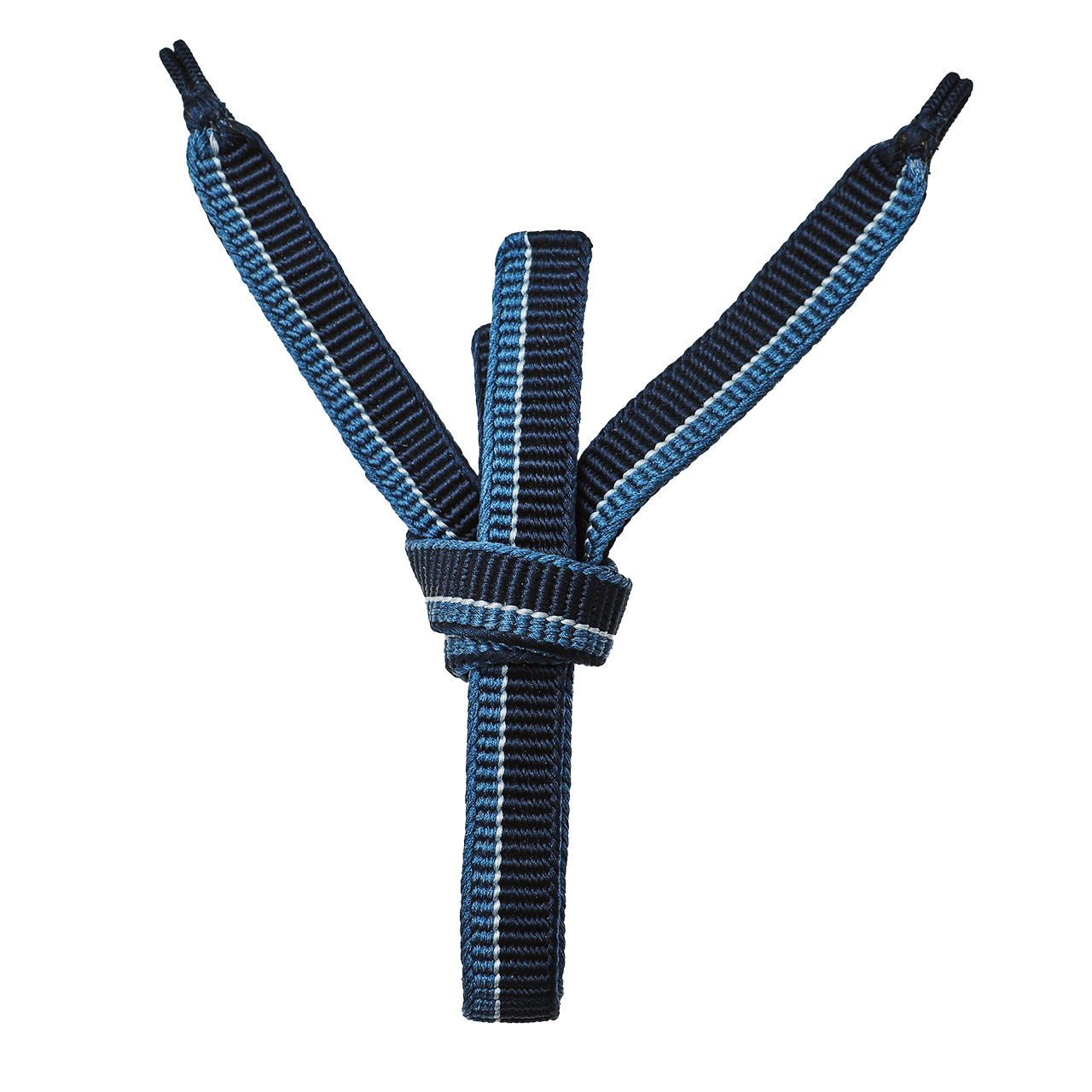

小物

小物

帯

帯

お召

お召

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

袴

袴

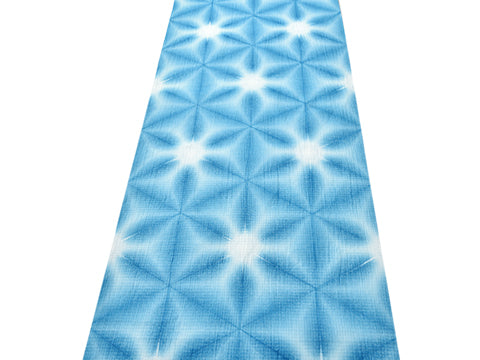

長襦袢

長襦袢

浴衣

浴衣

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

額裏

額裏

肌着

肌着

履物

履物

紋付

紋付

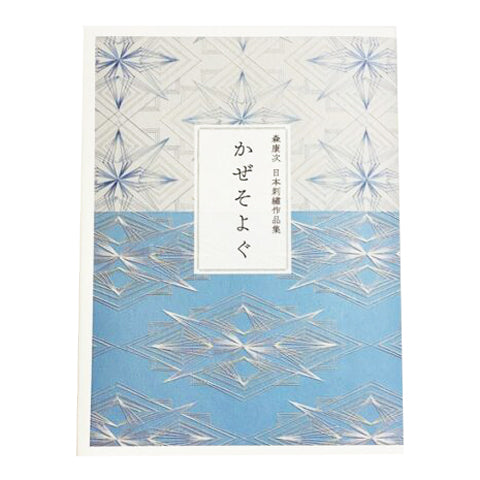

書籍

書籍