Edo komon dyer Kikuchi Hiromi is a modern trail-blazer working from her own studio, Yoshikiku, in Isesaki, Gunma. Having left a successful career with a major electronics firm, she became the sole apprentice to the late master Aida Masao, spending thirteen years absorbing his insistence on “making work for the present”. Since striking out on her own, she has reimagined classic Ise-katagami patterns through subtle shifts of tone, inventive colour palettes, and thoughtful fabric pairings, earning repeated selections at the Traditional Craft Exhibition and mounting her first solo show at Ginza Motoji in 2016. Today she personally handles every stage of production from stencilling, dyeing, steaming, and finishing the bolt, bringing fresh feminine vitality to this centuries-old technique.

In advance of “Kikuchi Hiromi: The Poetics of Edo Komon” (15-17 September 2023), we visited Yoshikiku for a close look at her process. The following article takes you on an in-depth tour of the studio, step by step, from blank fabric to finished bolt.

*This text was translated in June 2025

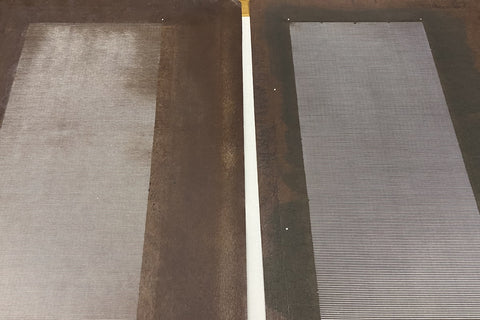

The long Fir board is a heirloom passed down from her mentor, Aida Masao, and is a treasured tool of the trade.

A seamless single plank without any knots, it allows her to dye even the most intricate patterns with confidence, the board itself dyed with the care and devotion of her late mentor, Aida Masao.

At the heart of the earthen-floored workspace stands a stately, timeworn board of fir. Stretching seven metres in length, it serves as the stage for katatsuke, the intricate stencilling process that lies at the core of Edo komon craftsmanship.

"When I became independent in 2011, Aida-sensei gave me two of the boards I had used during my apprenticeship," she recalls.

The straight-grained fir board is highly prized for its ability to naturally regulate the moisture content of the resist paste. Even the slightest knot can cause unevenness that disrupts the pattern, which is why Kikuchi still relies on this board when working with especially fine designs.

To prevent the paste from drying too quickly, no heating or air conditioning is used in the itaba workspace throughout the year. During the summer, she often shifts her working hours to the cooler nighttime, though she notes that in recent years, even the nights have remained uncomfortably warm.

She lifts the board using a lever-like motion, hoisting it from the centre point as a fulcrum.

Traditionally, work in the itaba, a humid space involving heavy lifting and physically demanding tasks was considered the domain of men. But Kikuchi’s mentor, Aida Masao, never subscribed to such conventions. “If you use the principle of leverage, women can do it too,” he would say, teaching the craft with no distinction between genders. At Kikuchi's suggestion, we staff members were invited to try lifting the treasured board ourselves, but we wobbled, staggered, and some of us couldn’t move it even a millimetre.

To prevent warping, the board is stored vertically, raised overhead when not in use.

Placing resist paste through an Ise-katagami stencil: katazuke, the very essence of Edo komon craftsmanship.

The production of Edo komon involves three main types of paste. First is nebanori, used to secure the fabric to the longboard. Then comes menori, the resist paste applied through Ise-katagami stencils to preserve the pattern in white. Finally, jinori is brushed over the dried resist to dye the background colour in a method called shigoki-zome. Kikuchi makes all of these pastes by hand, carefully adjusting their consistency to suit each step.

A handmade paste made by dissolving glutinous rice flour in hot water, affectionately known as neba (sticky).

A thin layer of nebanori is first spread across the board, then left to dry. When lightly re-moistened with a spray, it creates just the right amount of tack, like the back of a postage stamp, to hold the fabric in place.

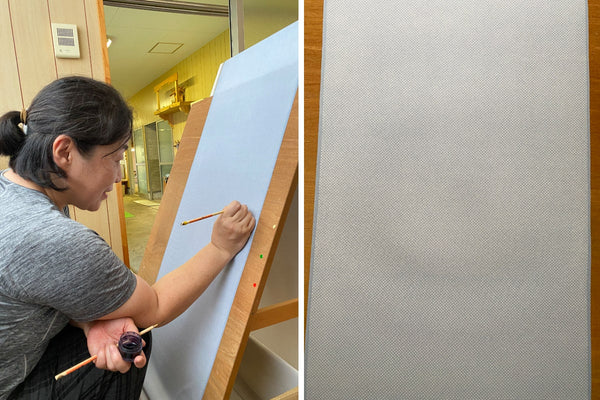

The cloth is carefully aligned to keep the weave straight, air is smoothed out from beneath, and the natural crepe texture of the silk fabric is gently settled. The edges are then adjusted to prevent lifting. This process, known as jigosuri, is essential for ensuring that the stencil lies flat and that the paste can be applied cleanly without damaging the delicate Ise-katagami.

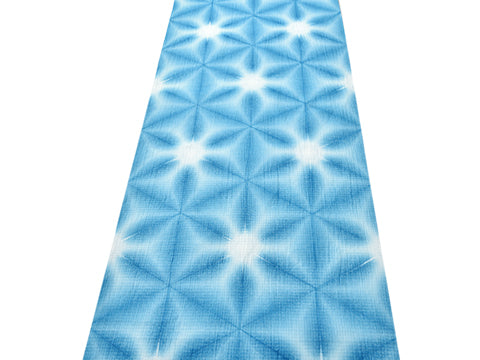

Once the fabric is secured, the process moves to the heart of Edo komon craft: katatsuke, the stencilling of patterns using Ise-katagami.

The base paste is made by steaming a mixture of rice bran, glutinous rice flour, and finely milled rice powder (jōshiro) for five hours. For menori, the resist paste used in stencilling, lime is added to this base. For jinori, the dyed paste used in shigoki-zome, salt is added to help fix the colour.

Menori, the resist paste used for stencilling.

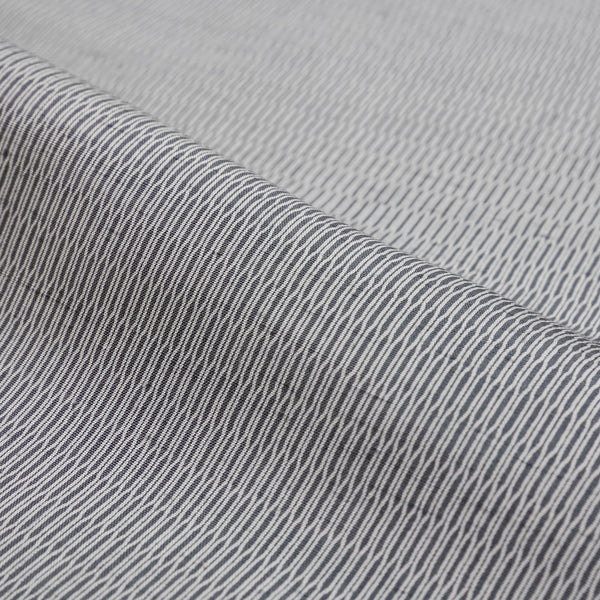

For patterned stencils, a stickier and softer paste is preferred. For striped designs, a firmer paste with a drier, crisper texture works better.

To make it easier to see how the stencilling is going, a water soluble pigment is added to the paste.

Each Ise-katagami stencil measures about 15 centimetres, and it takes roughly 90 perfectly aligned applications of paste to cover a 13-metre length of fabric. The process demands extended periods of intense focus.。

“If too much time passes, the colour of the paste changes and the stencilling becomes uneven, so I always make sure to finish the katatsuke within the same day,” she explains.

Kiribori, tsukibori, shimabori, dōgubori; each carving style brings out a different facet of the Ise-katagami’s expressive potential.

There are four main cutting techniques used in Ise-katagami, each handled by specialist artisans depending on the pattern.

Cutting techniques for Ise-katagami

-

Kiribori

A semi-circular blade is rotated to punch tiny half-moon holes. Typical patterns: same-komon, gyōgi, tōshi, arare. -

Tsukibori

The oldest method. A small knife is pushed straight down through the paper, cut by cut. -

Shimabori (also called hikibori)

Used for stripes. The names of stripes change based on how many stripes fit within a 3 cm width. The finest, mansuji, and the less dense kegoma. -

Dōgubori

The chisel itself is shaped like the motif—flower, diamond, fan, and so on—so one press cuts out the entire design.

Each of the four carving techniques once had its own Living National Treasure. Although no individual currently holds that title today. The Ise Katagami Technical Preservation Society was recognised in 1993 as the official custodian of this Important Intangible Cultural Property. Despite the craft’s great historical and cultural value, a shortage of successors now places its future at risk.

Both are stencils for striped patterns, but they differ in the number of stripe lines within a 3 cm width.

“Just as Japanese silk has become precious, so too have the stencils,” says Kikuchi Hiromi, who supports the Ise-katagami production region but also voices concern for its future.

“The current carvers tend to stay behind the scenes, treating the stencil purely as a tool. But I believe their names deserve more recognition.”

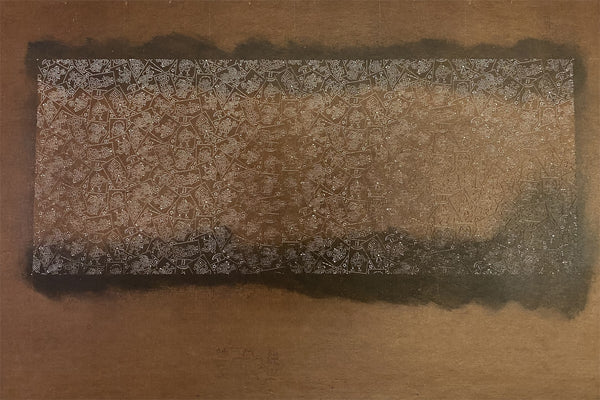

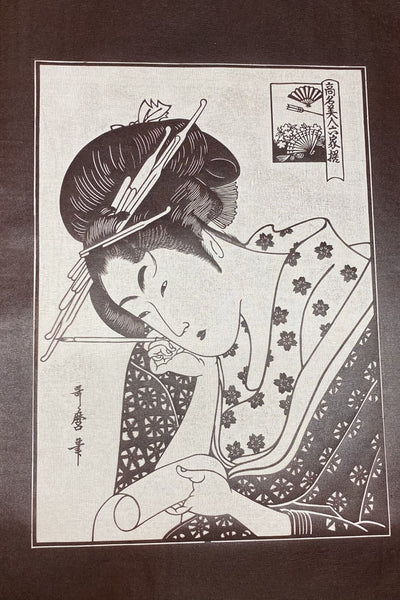

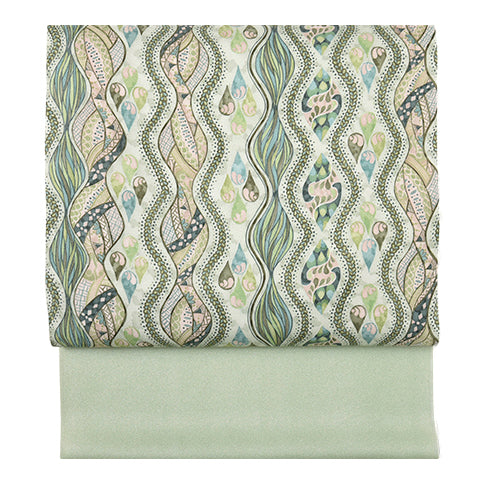

Ise-katagami stencil “Otsue”, carved by Rokuya Yasuhide (六谷泰英)

As a maker, Kikuchi believes in putting names forward—to spark wider interest in Ise-katagami among people today and to create more opportunities for the work to be seen.

True to that spirit, the comments she shared for this exhibition include the names of the stencil carvers alongside her own.

Ise-katagami stencil “Omeshi-jū”, carved by Imasaka Chiaki.(今坂千秋)

Kikuchi also believes in elevating the names of the other makers who's work supports her process. True to that spirit, the comments she shared for this exhibition include the names of the stencil carvers alongside her own.

Ise-katagami stencil “Bijin-zu”, carved by Uchida Isao.

Based on an old stencil, this design was newly re-cut.

"Some stencils are by unknown hands, but the designs and carving are still remarkable. When I see a stencil that moves me, I feel a strong urge to express that emotion and share it with others."

The distinct colours of Kikuchi Hiromi.

After katatsuke and shigoki-zome, the fabric is steamed to set the colour. Once the resist paste is washed off, the final step is jinaoshi, where any unevenness in colour, such as at stencil joins, is carefully corrected.

After the coloured paste is applied, the fabric is placed in this steaming chamber to set the colour.

Many fans who are captivated by Hiromi Kikuchi's work often say, “I love the colours of Kikuchi-san’s Edo komon.” Though they may appear to be black, they’re not just black; though they seem purple, they’re more than just purple. These solid colours somehow carry a depth that reveals a whole spectrum. Her nuanced palette, paired with meticulous fabric preparation, transforms even the most traditional patterns into truly one-of-a-kind Edo komon.

When the resist paste is placed, a she corrects any gaps in the paste by hand. She spends twice as long on this stage as she once did as a trainee.

Masao Aida often used to say to her, “Kikuchi-chan, it’s all about refinement.”

No matter how stylish a piece may be, he believed that without refinement, it fails to truly express anything.

That sense of dignity, he taught, is not just about the work itself, it reflects the heart behind the creation, and ultimately, how one lives as a person. He imparted this not through words alone, but through the way he lived and worked.

Perhaps this is why Kikuchi’s kimono with their monochromatic colour schemes, with their fine repeating patterns, manage to move those who see and wear them. Each piece begins from that very lesson.

Ushikubi Kimono "Rush"

名古屋帯

名古屋帯

袋帯

袋帯

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

浴衣・半巾帯

浴衣・半巾帯

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

肌着

肌着

小物

小物

履物

履物

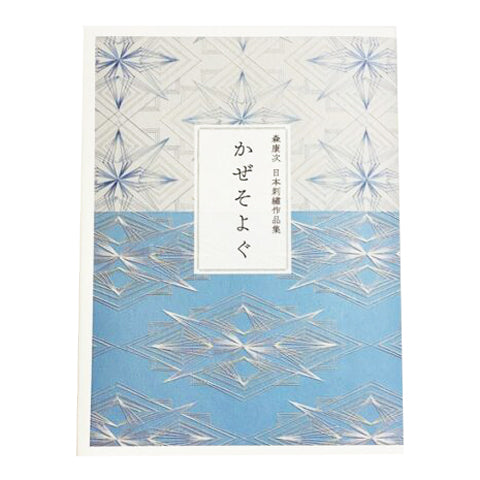

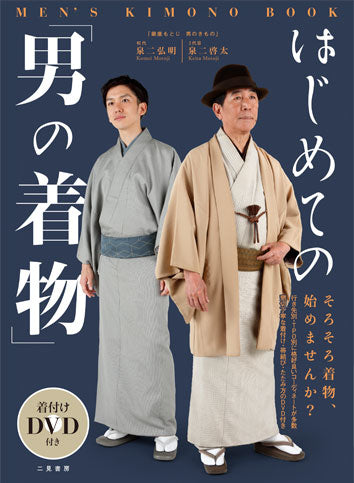

書籍

書籍

長襦袢

長襦袢

小物

小物

帯

帯

お召

お召

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

袴

袴

長襦袢

長襦袢

浴衣

浴衣

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

額裏

額裏

肌着

肌着

履物

履物

紋付

紋付

書籍

書籍