Written by Mark McNulty of Ginza Motoji

All Photos are original unless stated otherwise.

Top Image - A view up the River Liffey, and The Ha'penny Bridge, taken from O'Connell Bridge

Several months ago in Ginza, Keita Motoji of Ginza Motoji spoke with Asano Hiroki of Shokuraku Asano, a Nishijin-ori weaving house in Kyoto. Hiroki had recently begun exploring Celtic patterns as inspiration for kaku-obi (men’s obi), noting how their intricate interlaced motifs seemed well suited to the narrow, continuous form of the obi. From this conversation grew a larger idea: to travel to Ireland to study these patterns at their source and to engage with Irish art and craft directly. When Okuzawa Yoriyuki of the Yuki-tsumugi company Okujun heard of the plan, he quickly decided to join, accompanied by a staff member, Ando-san. In the end, five of us set out together, gathering in Dublin to begin the journey.

Although cultural ties between Japan and Ireland remain relatively few, there are touchpoints that Japanese audiences know well: From writers like James Joyce, and Oscar Wilde, to musician like Enya, and Bono too, the stylish Aran knit that alwaysseems to rings a bell, the Irish whiskeys that line the shelves of Ginza’s best bars, and, not to be forgotten, Guinness. There are also figures of historical connection, such as Lafcadio Hearn, the Irish writer who settled in Japan in the late nineteenth century and became one of the first interpreters of Japanese culture for the West, and Thomas Waters, an Irish architect who played a formative role in the modernization of Meiji-era Japan, remembered in particular for his work in Ginza as well as in Amami Oshima.

For Keita Motoji, this was his first visit to Ireland in nearly twenty years; for Asano-san, Okuzawa-san, and Ando-san, it was their very first time. For me, it was a return home with a fresh lense to look through. The anticipation was high. Opportunities to experience Irish culture directly are rare in Japan, and to step into that world together promised the beginning of something memorable.

Day 1 – Dublin

Trinity College, Parliment Square By David Kernan

Trinity College, Parliment Square By David Kernan

Our trip began inside the main gate of Trinity College, beneath the Campanile. We paused to take in the breadth of the courtyard and the contrasting architectural styles of the buildings that framed it. What impressed everyone most was the sheer age of the place, since Trinity College was founded in 1592 and many of the surrounding buildings have stood for centuries. From there, we made our way to the National Gallery of Ireland, where the collection offered a vivid introduction to the country’s artistic heritage.

We were especially struck by the luminous stained-glass windows of Harry Clarke, which seemed to nearly come alive in their jewel tones. We also admired the portraits of Sir John Lavery, whose works captured both Irish life and cosmopolitan society with elegance and depth. Walking through the quiet galleries, we felt the richness of Irish visual culture, spanning everyday scenes of peasants in a Connemara cottage to the portraits of the English gentry who had ruled our country unforgivingly for so many years.

William John Leech (1881-1968), A Convent Garden, Brittany, c.1913. Photo © National Gallery of Ireland.

William John Leech (1881-1968), A Convent Garden, Brittany, c.1913. Photo © National Gallery of Ireland.

From there we went to the National Museum of Archaeology, where Ireland’s deep past unfolded before us. Among the most extraordinary objects was the Tara Brooch. We had seen it countless times in books, yet standing before it in person was breathtaking despite the fact that it is almost impossibly small. The detail is so extremely fine, every minute pattern crafted with microscopic precision. Nearby, we marveled at the Early Bronze Age gold hoards: thin hammered lunulae and bangles decorated with intricate designs carved entirely by hand. To think that over three thousand years ago, artisans achieved such sophistication is truly inspiring.

The Tara Brooch, a 7th-century Irish masterpiece only 7 cm wide, dazzles with its astonishingly intricate gold filigree and inlaid detail. Picture; Wikipedia

The Tara Brooch, a 7th-century Irish masterpiece only 7 cm wide, dazzles with its astonishingly intricate gold filigree and inlaid detail. Picture; Wikipedia

In the evening, we returned to Trinity College to see the Book of Kells, a manuscript of the Gospels produced more than a millennium ago on vellum (sheepskin parchment) with natural pigments. The colours remain remarkably vivid, and the preservation is extraordinary. As the book is extremely fragile, a page is turned every day. The page we saw though extremely beautiful was one of the simpler pages, despite this we were impressed by the vividness of the blues and by the depth of the iron gall ink.

Extraction from The Book of Kells. Picture; Wikipedia

Extraction from The Book of Kells. Picture; Wikipedia

Afterwards, we entered the Long Room, Trinity’s iconic library hall. With its soaring barrel-vaulted ceiling, dark wooden shelves, and ranks of marble busts, the space carried both grandeur and a sense of transition. Most of the historic volumes had recently been “decanted” for conservation during the Old Library redevelopment, leaving the shelves strikingly bare. At the far end, Luke Jerram’s monumental sculpture Gaia, a seven-metre-wide glowing replica of the Earth, hovered in the nave and gave the room an almost otherworldly presence. Alongside the traditional line-up of male writers and philosophers, 6 new busts of female literary figures have also been introduced, including writer and playwright Lady Gregory, signalling a more inclusive narrative within this iconic hall.

Day 2 – Newgrange, Clonmacnoise, and Galway

With our first day in the city enjoying the various galleries and museums, we hit the road. We were blessed with fantastic weather, a rarity in Ireland to have a whole day so bright and clear. As it was early August, the days were long, with the sun rising early and setting just after nine.

Our first stop was Newgrange, a monumental passage tomb built around 5,000 years ago during the Neolithic period. It is renowned for its alignment with the winter solstice sunrise, when sunlight penetrates deep into the inner chamber. Recognized as one of the oldest surviving structures in the world, it is also a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Left: One of the 97 Kerbstones Right: Entrance to the Tomb

Left: One of the 97 Kerbstones Right: Entrance to the Tomb

We then drove another two hours to Clonmacnoise. Founded in the sixth century by Saint Ciarán, it was once a major center of learning and faith in Ireland. Today the site preserves round towers, stone churches, and intricately carved high crosses, offering a vivid glimpse into the island’s early Christian heritage.

As we continued driving westward, the scenery grew increasingly dramatic. This land was flattened by glaciers millions of years ago, leaving only a thin layer of soil. Few trees grow here, and massive rocks and boulders emerge starkly from the ground. Stone walls lined the winding roads, creating a distinctive and rugged beauty. Finally, as the sun was setting, we arrived in Galway where we enjoyed good food and traditional music.

Day 3 – Inis Meáin, the Aran Islands

The following morning, we took a ferry of about an hour and a half that made two stops: the first at Inis Meáin, and the second at Inis Oírr. Only a handful of passengers got off at Inis Meáin with us, and for much of the day we felt as though we had the island almost to ourselves.

From the small port we looked up to towards the gently sloping island, its distinctive landscape, where thousands of kilometres of stone walls crisscross the ground. For centuries, the people of Inis Meáin have adapted ingeniously to their environment: breaking stones to create walls that act as both boundaries and windbreaks, and carrying sand and seaweed from the shore to slowly build soil upon the rocky surface. Thanks to this patient labour, crops such as potatoes, carrots, and onions took root, and livestock such as sheep and cattle were raised. With no peat or trees for fuel, islanders historically traded their produce with the mainland. OEven today, the island remains small and close-knit, with just one pub, one shop, and one church.

Our first stop was the Inis Meáin Knitting Factory, the biggest employer on the island and where the island’s long tradition of Irish knitwear continues. Today, hand knitters are rare, and most sweaters are machine-knit before being hand-finished. Irish wool can be coarse, so imported yarns are often used to create garments that are softer and more luxurious. The designs blend traditional Aran patterns with contemporary styles, and the sweaters are exported worldwide.

Left: Logo of Inis Meain Kitting. Right: a rocky ledge covered in Nasuritums, with a typical rock wall in the backround.

Left: Logo of Inis Meain Kitting. Right: a rocky ledge covered in Nasuritums, with a typical rock wall in the backround.

Next we visited Teach Synge, the small traditional stone house where playwright John Millington Synge once stayed. Whitewashed and once thatched, the home was faithfully restored, with a handmade wicker basket by the hearth, a traditional red skirt and crois (a handwoven woolen sash, worn at the waist like an obi) hanging on a wooden peg, and ceramics displayed in a cabinet. One jug even showed a figure resembling a Japanese geisha, while another plate bore the famous “Willow” pattern a reminder that Japonism can be found in the most unexpected corners of the world.

Left - A similar sideboard with Willow Pattern Serving Dish.

Photo from courtesey of National Museum of Ireland

Right - Whitewashed walls of Teach Synge

Across the road stood Séipéal Mhuire Gan Smál (Church of Mary Immaculate), built in 1939. Its stone walls rose prominently above the low landscape. Inside, the nave glowed with stained-glass windows by the Harry Clarke Studio: the east window showing the Virgin and Child, the side windows portraying saints. Even the Stations of the Cross were inscribed in Irish, emphasising the island’s strong cultural identity.

Left and Right : Séipéal Mhuire Gan Smál with Harry Clarke Windows

We then made our way to Dún Chonchúir, a large oval stone fort dating to around the first millennium BC. Its massive drystone walls, still standing after thousands of years, testify to the endurance of human settlement on this remote island.

Finally, we hiked along the cliffs, where the Atlantic crashed against the rocks below. As the sun lowered, a local gave us a lift back to the harbour. Boarding the ferry once more, we sailed back across the sea, driving through Connemara’s winding roads toward Donegal, with the last light falling over the peak of Benbulben.

Day 4 – Donegal, Ardara Tweed, and the Giant’s Causeway

Our journey took us to Donegal, a small town whose center is called the Diamond. From there we drove north to Ardara, a town famous for its history of Irish tweed weaving. We visited one of its most renowned producers, Molloy & Sons, where Kieran Molloy generously showed us around their workshop. He explained not only the long history of tweed in the region, but also its contemporary place in fashion culture.

Left : A text on the history of Molloy Tweed picture of office in New York. Right: Thread samples

We learned about the features that make tweed unique: classic weaves such as herringbone and plain weave, and the use of colourful neps that bring plain-coloured threads to life. As with knitwear, Irish wool can often be too coarse for luxury-level suiting, so Molloy & Sons frequently use fine wools imported from across Europe to create textiles of international quality.

From Ardara we continued north towards Belfast. Just over the border, our journey was briefly interrupted by a punctured tyre. As we waited on a grassy bank for the repairmen to arrive, we enjoyed a panoramic view of the Binevenagh Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, with its dramatic cliffs and expansive landscapes.

Our final stop of the day was the world-famous Giant’s Causeway. This UNESCO World Heritage Site consists of around 40,000 interlocking basalt columns, formed some 50–60 million years ago by ancient volcanic activity. The striking hexagonal shapes have inspired countless legends, the most famous being that the columns were built by the giant Finn McCool to cross the sea to Scotland. Standing among these surreal formations, it was easy to see how geology and mythology intertwine in Ireland’s cultural imagination.

Left: Giant’s Causeway. Right: heather in bloom, its tiny flowers spreading a purplish haze across the Irish hills.

Day 5 – Dublin

On our final day in Dublin, we wandered through the city in rare sunshine, taking in the redbrick townhouses and lively streets. At the Chester Beatty Library we encountered art from across the world, including Japanese ukiyo-e. The city itself was buzzing, awash with Oasis T-shirts as fans gathered for that evening’s concert.

As the sun set, we slipped into a pub off St. Stephen’s Green. Traditional music played before us, and over a few pints of Guinness we looked back on what we had experienced in Ireland. One impression that stayed with us was the stark difference between the country scenes and those of Japan. Japan, with its high, steep mountains and deep green foliage, felt worlds apart from Ireland’s bright, low-lying fields, dotted with grazing livestock, old oaks, and the stone ruins of centuries-old castles.

We began to wonder how such landscapes, as well as the other things we saw might find their way into our own making. Could the irregular texture of nepped threads seen in Donegal Tweed be carried into Yuki Tsumugi? How might the subtle greens of moss and heather seen on the island of Inis Meain be re-imagined in Nishijin-ori?

In the months ahead at Ginza Motoji, we will share new work shaped by these questions. The exhibition will feature Nishijin-ori by Shokuraku Asano, shown alongside kimono from the Yuki Tsumugi weaving house Okujun, works that trace a path from Ireland back into Japanese textile practice. We look forward to turning what we found in Ireland into something new to wear, a kimono that carries both worlds within it.

2025/09/11

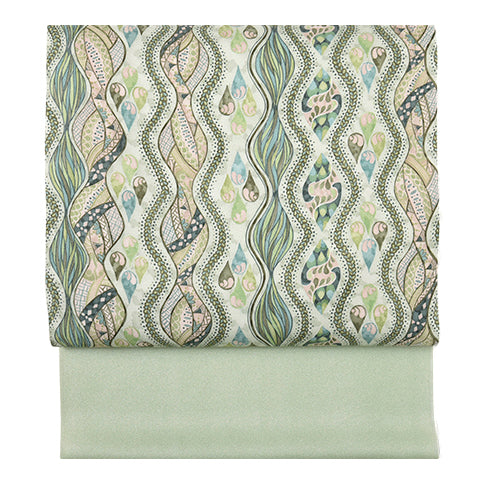

About Shokuraku Asano

Founded in 1980 with the concept of "Enjoying Weaving," Shokuraku Asano is a Nishijin-ori weaving brand with a remarkable legacy. Including its predecessor, "Asano Oriya," the brand marks its 100th anniversary in 2024.

With stunningly refined designs and unparalleled ease of use, Shokuraku Asano's works enjoy immense popularity. In fact, our staff rely on them so often that we've coined the phrase "When in doubt, Shokuraku"

With just one of Asano's obi, a tsumugi kimono transforms into a polished look, classical yawarakamono kimono pieces take on a modern feel, and forlorn inherited kimonos gain a contemporary flair. Shokuraku obi possess a unique power to harmonize kimonos with today’s urban landscapes, striking a balance that feels just right.

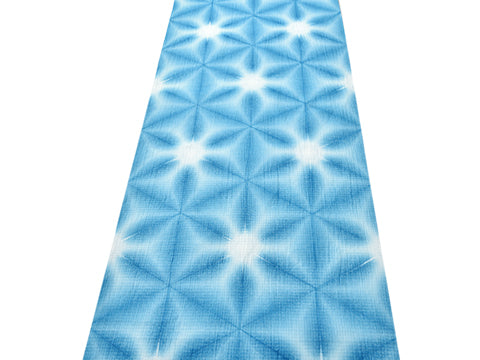

About Okujun

Founded in 1907 in Yuki , Ibaraki , Okujun Co., Ltd. is a leading producer of Yuki-tsumugi, a UNESCO-recognized silk weaving tradition. The company oversees every stage of production, from hand-spun floss silk yarns to weaving on traditional back-tension looms. Alongside preserving the heritage of Honba Yuki Tsumugi, Okujun also develops accessible lines such as Yuki Silk, balancing tradition with innovation. Through initiatives like the Tsumugi Silk Museum, they continue to safeguard and share this craft with future generations.

名古屋帯

名古屋帯

袋帯

袋帯

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

浴衣・半巾帯

浴衣・半巾帯

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

肌着

肌着

小物

小物

履物

履物

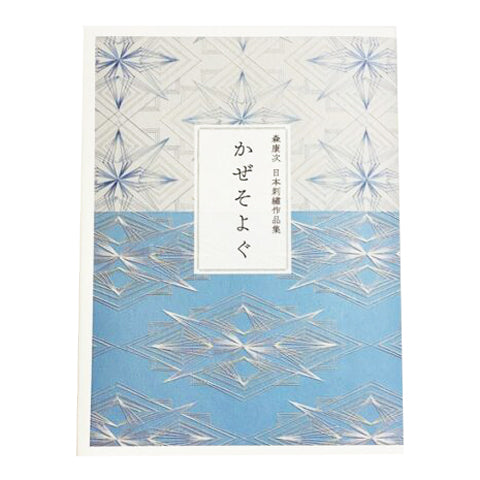

書籍

書籍

長襦袢

長襦袢

小物

小物

帯

帯

お召

お召

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

袴

袴

長襦袢

長襦袢

浴衣

浴衣

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

額裏

額裏

肌着

肌着

履物

履物

紋付

紋付

書籍

書籍