Author - TODATE, Kazuko

When discussing the yuzen artist Kunihiko Moriguchi, it is natural to refer to his father, Kakou Moriguchi (1909–2008).

Both father and son are holders of the title Important Intangible Cultural Property in yuzen, there exists a contrasting dynamic between them: Kakou’s “representational” style versus Kunihiko’s “abstract” one, or the way Kakou celebrated nature’s forms compared to Kunihiko’s dedication to geometric shapes. This contrast provides an easy framework for describing them.

However, in revisiting Kunihiko Moriguchi’s collection work created over nearly fifty years, one begins to see a deeper essence of his artistic world that transcends such simple contrasts. Additionally, the significance of his journey through the Shōwa, Heisei, and Reiwa eras comes into focus.

During my time as a curator, I first handled a yuzen kimono by Kakou Moriguchi, and later had the opportunity to display works by Kunihiko Moriguchi. Through this current exploration of Kunihiko Moriguchi’s art, I expect to naturally reveal not only the differences in their work but also the underlying elements that connect the two artists.

Born in Kyoto...

Kunihiko Moriguchi was born in 1941 in Nijō, Kyoto, the second of three siblings. Unlike many traditional Japanese families, the Moriguchi family did not hold conservative expectations about the eldest son inheriting the family business. His elder brother pursued architecture and now works in design and project management. Two years before Kunihiko’s birth, his father Kakou had gained independence from his teacher, the third-generation yuzen master Nakagawa Kason, and chose to focus on studying the yuzen technique of makinori*. Although examples of makinori are found in Edo-period yuzen textiles in the collection of the Tokyo National Museum, it was Kakou’s work that revived, developed, and popularized this technique, marking one of his significant contributions to the craft.

(*Makinori is a technique where dried nori is crumbled and sprinkled onto the fabric. the fabric has been preprepared with masking tape, and when its removed, a sharp line between the solid color and spotted pattern appears.)

In 1939, Kakou became an independent Yuzen artist. Yuzen was traditionaly a collaborative process, with different people to execute every step of the process. His move was groundbreaking in Kyoto’s traditional textile world, where establishing oneself as an independent maker was seen as challenging.

“Kakou was not just my father; he was the father of modern yuzen dyeing”

Kunihiko said (*Note 1).

This statement reflects not only his respect for his father but also an undeniable truth from a broader perspective of the kimono world. Japanese textile arts shifted from specialized teams in workshops to individual artists.

Kunihiko grew up with a sense of freedom under his easygoing father’s influence. His first means of creative expression was photography. At the age of 16, he receiveda second-hand German camera from his father, a Rolleicord, with which he began taking photos. This may have been Kakou’s way of entrusting his son with a passion of his own youth, as he himself had loved photography. Moreover, this experience likely nurtured Kunihiko’s early interest in “human vision.” The world viewed through a lens offers a perspective distinct from what we see with the naked eye.

*Note 1: Interview with the author, July 5, 2019, at Kunihiko Moriguchi’s residence in Kyoto. All quotations from Kunihiko in this text are from this interview.

Avante-Garde in Kyoto

Artists and makers have been gathering in Kyoto for a long time,. and as Kunihiko Moriguchi reached adolescence, he aspired to become a painter and studied Japanese painting under the guidance of Domoto Insho.

In the Kansai region from the late 1940s to the 1960s, a major wave of Japanese avant-garde art was emerging. The Gutai Art Association was founded in 1954, and one of its leading artists, Kazuo Shiraga (1924–2008), came from a family of kimono merchants. In 1963, a textile group called "Mugendai" (Infinity) was formed in Kyoto to explore the world of topological abstraction. According to its members, “Mugendai” aimed to carry forward the legacy of Inagaki Toshijiro (a Living National Treasure for kataezome stencil dyeing) and a professor at Kyoto City University of Arts, who passed away in 1963. There was a growing movement in the world of textiles to seek new forms, particularly abstract expressions that also intersected with the world of graphic design. This movement, which grew out of traditional kataezome techniques like those of Inagaki, felt distinctly Kyoto-esque in its connection to the established arts. Even as the avant-garde sought to break from the past, one could not ignore the profound historical roots of dyeing and Japanese art that were deeply ingrained in Kyoto.

And to France...

Pursuing his passion for painting, Kunihiko Moriguchi entered the Japanese Painting Department at Kyoto City University of Arts, where he studied under prominent painters such as Shōkō Uemura, Shihō Sakakibara, and Fuku Akino. Although pop art from the United States was popular even within the university at the time, Moriguchi felt a disconnect with it. His fascination with painting was reignited when he saw works by artists like Corot at an exhibition of French art at the Kyoto City Museum of Art, prompting him to decide to study in France. Alongside his university classes, he learned French at the Kansai Franco-Japanese Institute, and in 1963, at the age of 22, he enrolled in the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. The school offered comprehensive foundational training, and Moriguchi worked on plaster drawing as well as creating small, approximately 50-centimeter sculptures of the human body. This training has continued to inform his current work in yuzen, particularly in understanding the relationship between the female form and patterns.

In 1960s France, as a counter to the wave of pop art, op art (optical art) was gaining attention, characterized by abstract art that uses visual illusions, with notable figures such as Victor Vasarely (1906–1997) and Bridget Riley (1931–). Moriguchi himself has said that Bridget Riley is one of his favorite artists. As a school assignment, he created the above illustration study piece using only black and white planes to make petal-like shapes appear to emerge from the background.

After graduating with flying colors from school in Paris, Moriguchi initially planned to stay in France and work as a graphic designer. However, the artist Balthus Klossowski de Rola (1908–2001), encouraged him in continuing his father’s legacy. Consequently, in 1966, Moriguchi returned to Japan. Interestingly, his initial motivation to go to France was inspired by landscape painters like Corot, who specialized in representational art, and the person who urged him to return was Balthus, a traditionalist in European representational painting. Moriguchi’s innate appreciation for the beauty of representational art, was likely a sensibility inherited from his father.

※第38回日本伝統工芸近畿展 出品作品(平成21年)

Training under his father, Kakou.

In 1967, the year after his return to Japan, Kunihiko Moriguchi began training in yuzen dyeing at his father's studio. Unlike his father, who created vibrant designs featuring trees and flowers like plum and chrysanthemum, with the delicate sprinkled paste technique as a foundation, Kunihiko chose a path of geometric abstraction from the start. A reason for this choice was undoubtedly that he felt he could not compete with his father’s skill in depicting nature. Reflecting on his father, Kunihiko recalls, “He would quickly mark out the entire kimono, then paint each detail with an intense focus. Even while working on one part, he could still see the whole piece. His speed and precision in painting were beyond anything I could achieve.”

Overwhelmed by his father’s extraordinary talent, Kunihiko even considered giving up yuzen altogether. When he told his father that he couldn’t carry on the legacy, His father reassured him by sharing his own experience: “We’re not a family with successive generations of artists; just do what you love.” Indeed, while Kakou had spent 15 years assisting Nakagawa Kason with intricate, vividly colored yuzen, after becoming independent, he reduced his color palette significantly, often favoring pink. His bold compositions featured natural subjects that leveraged the makinori technique across the entire kimono, resulting in a simpler style. While under Kason, he worked on classical, auspicious motifs, but after going independent, he expanded his repertoire to abstract designs based primarily on “lines.” His work *Light* (1964), which uses only resist paste lines and a makinori ground to create an almost plain background, exemplifies this approach. Kakou too, had created “as he liked,” as an artist in his own right.

Kunihiko’s near-exclusive dedication to geometric abstraction reflects not merely a passive desire to avoid comparison with his father but a similar drive to establish his own artistic world. His early works demonstrated confident abstract expression, likely due to Kahiromu’s respectful, non-interfering approach toward Kunihiko as a fellow creator.

Kunihiko Moriguchi and his Optical Illusion Kimono

Metamorphosis, from ground to pattern.

Kunihiko Moriguchi’s memorable first entry in the 14th Japan Traditional Art Crafts Exhibition, “Light” (1967), showcased a design based on squares, with the figure and ground gradually merging in equal balance from the right sleeve down to the left hem, with the rich crimson hue transitioning to a lighter tone overall. In his piece “Senga” (1969), exhibited at the 16th exhibition, hexagonal motifs with three connected petal shapes fade from the hem to the shoulder, with the lines becoming finer and lighter, causing the hexagonal shapes to eventually disappear. This effect evokes a world akin to visual illusions, similar to the work of Escher’s.

This metamorphosis of figure and ground by gradually changing the scale of motifs and adjusting color tones and contrast has remained a defining characteristic of Moriguchi’s work, applied to various basic shapes with a conscious awareness of the kimono’s form. His works evoke elements of not just optical, but kinetic art too, as the viewer must move their gaze to appreciate the shifting patterns rather than focusing on a single point. The impact of this transformation displayed on a life-sized kimono is also essential.

Utilizing Yuzen Techniques—Organic Geometric Abstraction with Makinori.

A second characteristic of Moriguchi’s work is his proactive use of yuzen techniques from the beginning of his career, notably sprinkled paste (makinori) and lines made with itome paste. Moriguchi’s pieces are often based on pure geometric shapes like squares or hexagons, creating a world that could theoretically exist in just black and white. In fact, the catalog images of his early works in the Japan Traditional Art Crafts Exhibition were monochrome, which might be frustrating for most textile artists, yet in Moriguchi’s case, even in black and white, the structure of his world was clear. His works represent ultra-avant-garde yuzen, as they could succeed without color.

However, despite this reductionist approach, Moriguchi’s works are thoroughly yuzen, brought to life through the specific techniques of sprinkled paste and itome paste. The texture of sprinkled paste adds a layer of organic quality to his pure geometric motifs, creating a “third color” between black and white. In this sense, even when his yuzen designs are black and white, they can be said to contain three colors. Furthermore, lines made with itome paste are extensively used in his geometric expressions, such as creating surfaces by gradually changing the width of the lines or by forming new shapes through the sequential placement of lines. The kimono he was working on during my recent interview also embodied this direction.

In the 1960s, geometric and abstract dyeing works in the avant-garde sphere often faced criticism, such as, “Why not just paint it?” or “What’s the necessity of dyeing here?” Indeed, some works felt lacking in depth despite the artists’ ambitions. In Moriguchi’s case, however, he skillfully employs yuzen techniques like itome paste and sprinkled paste, giving his works a depth, spatiality, presence, and dignity that go beyond mere surface design. His strong foundation in yuzen technique supports the complexity, spatial depth, and substantial presence of his work.

Developing Designs—Kimono-Specific Design and Composition, and the Female Form

Although Kunihiko Moriguchi never received advice from his father on design, nor did he learn techniques directly from him, he often sought feedback from his father on his draft sketches. Even Kahiromu’s work contains examples of visual illusions, such as in *Chirimen Yuzen Kimono “Sound of the Sea”* (1972), where the ground and figure reverse in a wave pattern, showing the possible influence of Kunihiko’s design ideas. Both Kahiromu and Kunihiko experimented with diverse focal points for their kimono compositions, but Kunihiko often placed a space resembling a portal to another dimension at the center of the kimono, as seen in his *Yukimai* (Snow Dance) (2016), where gradients cross in an X-pattern rather than in a single direction.

Moriguchi meticulously organizes and archives all of his past designs. Some designs that could not be used for kimono when initially created may be refined years later to suit the garment. He revisits and develops his ideas regularly.

Regarding kimono design, Moriguchi focuses not only on the appearance when displayed on a rack but also on how the design wraps around a woman’s body, with patterns spiraling around her form, offering double the enjoyment of the design. He describes the kimono as “armor for women, a tool for self-transformation.” His kimono embodies a sense of cool beauty.

In the current exhibition celebrating the 40th anniversary of Ginza Motoji, Moriguchi’s works include both geometric patterns that maximize the form of the kimono and designs with strategically placed representational flowers. The exhibition undoubtedly showcases yuzen kimono as outfits that enhance the intelligence of the women who wear them, offering a true sense of elegant empowerment.

Kunihiko Moriguchi - Chronology

- 1941: Born in Kyoto.

- 1963: Graduates from Kyoto City University of Arts, Department of Japanese Painting, and travels to France as a French government-sponsored student.

- 1966: Graduates from the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs in Paris.

- 1967: Begins working in yuzen dyeing under his father, Kahiromu Moriguchi.

- 1969: Receives the Commissioner for Cultural Affairs Award at the 6th Japan Dyeing and Weaving Exhibition and the NHK President’s Award at the 16th Japan Traditional Art Crafts Exhibition.

- 1988: Awarded the Chevalier of Arts and Letters by the French government.

- 2001: Receives the Medal with Purple Ribbon.

- 2007: Recognized as a holder of Important Intangible Cultural Property for “Yuzen.”

- 2009: Exhibition of Kahiromu and Kunihiko Moriguchi – Father and Son, Living National Treasures (Shiga Prefectural Museum of Modern Art and Yomiuri Shimbun Tokyo Headquarters).

- 2013: Receives the Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays with Rosette.

- 2016: Kunihiko Moriguchi – Hidden Order exhibition at the Japan Cultural Institute in Paris.

TODATE, Kazuko - Profile

Born in Tokyo in 1964, Todate has extensive experience as a museum curator, a professor at Tama Art University, craft critic, and craft historian. Starting with Tate St Ives in the UK, she has supervised international exhibitions such as Forms of Handcraft, at institutions including Smith College in the United States and the Frankfurt Museum of Applied Arts in Germany. She has authored works including Katsuma Nakamura and the Lineage of Tokyo Yuzen. Todate writes a column titled "From the Horizons of Craft" in the Mainichi Shimbun (second Saturday of every odd-numbered month)

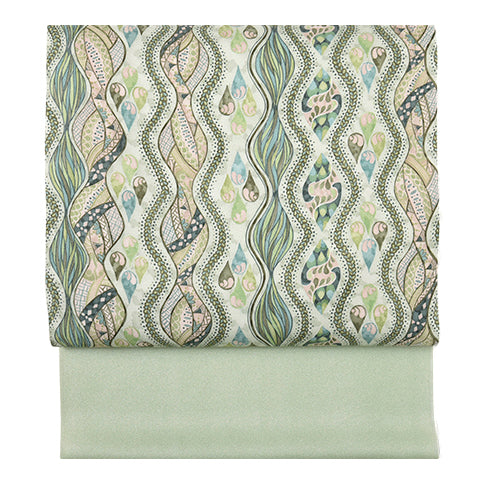

名古屋帯

名古屋帯

袋帯

袋帯

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

浴衣・半巾帯

浴衣・半巾帯

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

肌着

肌着

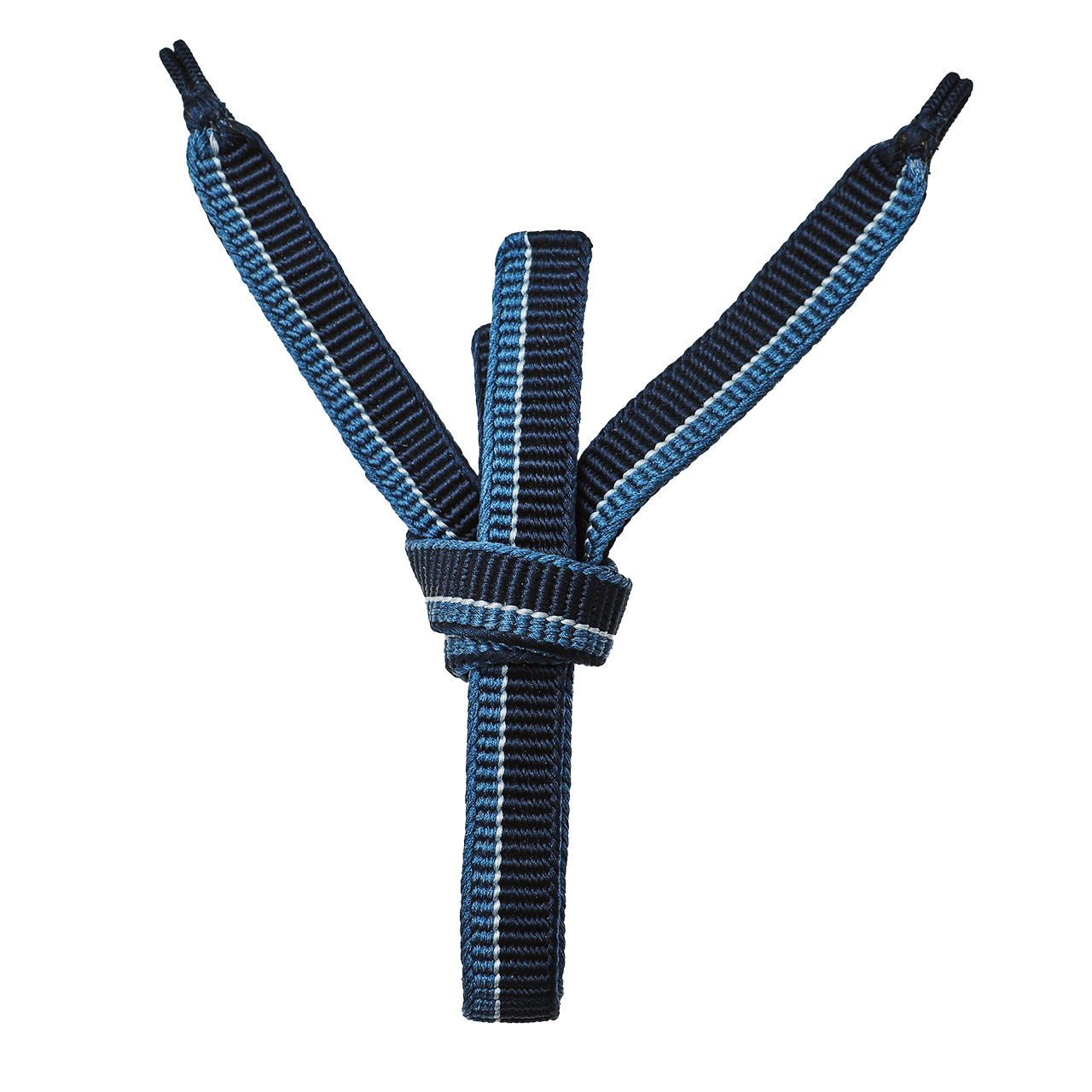

小物

小物

履物

履物

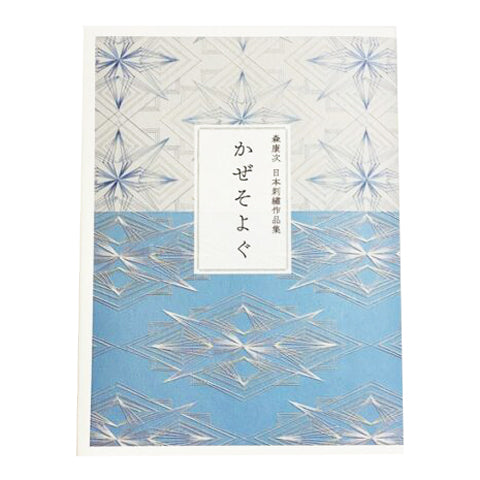

書籍

書籍

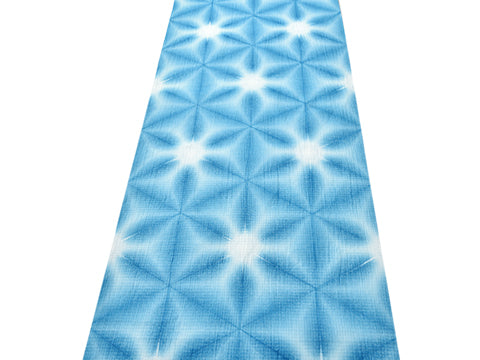

長襦袢

長襦袢

小物

小物

帯

帯

お召

お召

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

袴

袴

長襦袢

長襦袢

浴衣

浴衣

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

額裏

額裏

肌着

肌着

履物

履物

紋付

紋付

書籍

書籍