Writer:TANAKA, Atsuko

When I first met Mori Yasutsugu, I expected “embroidery” to mean traditional techniques, suga-nui(菅繡), sagara-nui(相良繡), matsui-nui(まつい繡)quietly added to kimono, obi, and haori. Instead I found exacting constructions in silk thread. “In the end, embroidery is about the arrangement and crossing of threads,” he said. That sentence rearranged my idea of the field.

Mori doesn’t merely embellish garments; he makes artworks that reveal beauty in two directions, toward the wearer, and back into the very fibre of the silk thread itself.

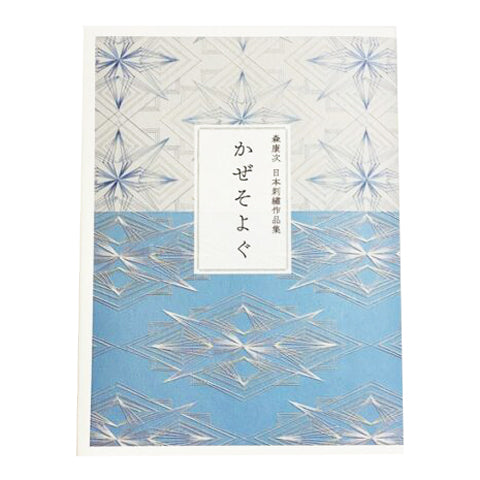

One example is his unwearable, framed series “Forms in Thread.” Twisted embroidery threads are neatly wound on a core rod and laid side by side; their careful ordering creates gradations where colour seems to appear and dissolve. The piece asks what embroidery thread can do when freed from the task of depicting.

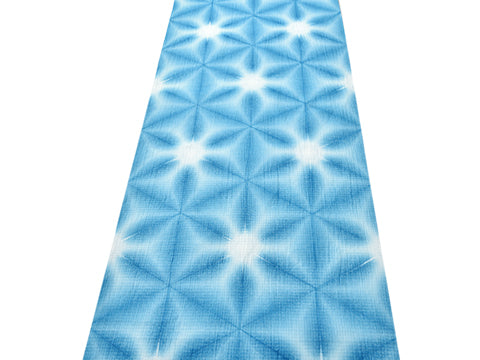

A companion group explores geometry born from crossings of thread “Intersection,” “Spiral,” “Light Trails.” Lines meet, pivot, and sweep until structure becomes image.

Seen together, these works make his point plain: if embroidery is the disciplined placing and crossing of threads, then Mori is showing that idea in its purest form.

Hagoromo - Fujin Raijin (Wind God Thunder God)

A New Form of Japanese Embroidery

Mori was born in 1946 into a nui-ya, an embroidery workshop in Nakagyoku, Kyoto. The family made their living from embroidery, one of the specialist trades that support Kyoto’s highly segmented kimono industry. Nakagyoku was a craftsman’s neighbourhood, where it is said you could have a kimono woven, dyed, embroidered, and tailored up all by the end of the day.

“Whether it was my parents, my older sister, or our staff, there was always someone sitting at the embroidery frame,” Mori recalls.

Scenes of embroidery were some of his first memories, and in those days it was assume that the firstborn son would inherit the trade. Mori began working in the family studio at the age of only 15, and In the post-war kimono boom there was no shortage of work. They were mainly occupied doing the finishing embellishments on dyed yuzen kimono.

“For a yuzen kimono, I might outline a chrysanthemum in kinkoma (goldwork), or on a plum blossom, I’d stitch the the stamens and pistil to ensure they would catch the light” he says.

Those small details are what give the flat surface dyed yuzen outlines a gentle relief and an extra level of dimension. Mori handled the steady flow of embellishment jobs.

“You have to do all sorts of things,” he says. “Even with first-time tasks, you learn as you go and get them done. Over and over.”

Within Japanese embroidery, there are many different types of stitches, but on top of this, Mori has also managed to master the art of manipulating the thread itself. This includes the twisting threads of different thicknesses together to create volume, form, and shadow.

“I didn’t even think it was hard. Work just came naturally.” he says frankly.

As he developed his skillset, simply embellishing the work of others work began to feel insufficient.

“Looking at old textiles, I realized that before yuzen emerged in mid-Edo (1700s), especially in the Momoyama period(1568 - 1600), kosode relied entirely on embroidery. Embroidery can carry the entire design. It can take center stage.”

Embroidery in Momoyama Japan reached a peak with techniques imported from the continent along with Buddhism. Densely filled surfaces in various motifs adorned those who could afford them over time into a distinctly Japanese approach that lets silk’s sheen breathe across the cloth. The beauty of Momoyama kosode still captivates viewers today.

Designs rendered entirely in embroidery, without yuzen, are called sunui, or pure embroidery. Though both are embroidery, this is a different world.

“With embellishment, skill is enough. A bolt arrives; if you embroider quickly and cleanly, the client is happy.”

Sunui, by contrast, starts from zero. You must source the cloth and study the garment’s shape, design, and colour. It is end-to-end making, which means authorship is required.

“Something radically new began for me.”

At 20, Mori studied kimono design under fashion designer Kaoru Matsuo.

“I felt I had to learn the structure of kimono and the image of it as clothing.”

He also took sketching and watercolor with painter Mutsuko Kuwano.

“I sketched constantly. I even put up a little motto: one drawing a day.”

He began to see many craft works in museums and open exhibitions, not only embroidery but dyed and woven pieces, fixing the styles he loved in his mind.

Contemporary embroidery artists also made a strong impact. He admired Keishun Kishimoto’s freedom with colour, composition, and fabric choice, and Ritaro Hirano’s beautiful lines and sense of depth.

At 39, he entered the Japan Traditional Kōgei Exhibition for the first time and was accepted on his first try. Securing a place to present his work let the possibilities of pure embroidery come into view.

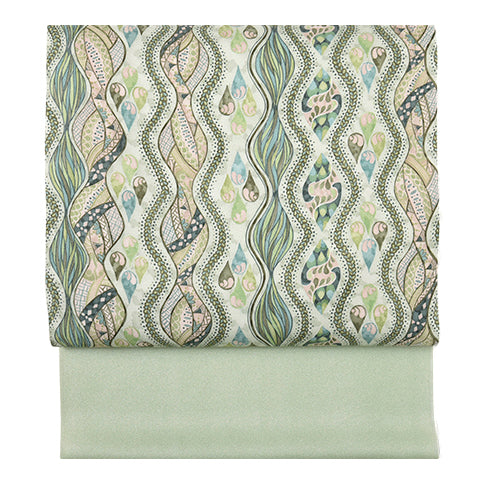

Platinum Boy Silk; Tsukesage Houmongi

(Left) Mitsuwari Kiko-mon「三ツ割亀甲紋」

His current workshop is in Kamigamo, Kita, Kyoto, where they moved in 1980.

Close to the Myojin-gawa stream that runs through Shake-machi and to streets of old houses, with a view toward Mount Hiei. Kamigamo Shrine, famous for the Aoi Matsuri, Ota Shrine with its wild kakitsubata irises, the Kamo River and its riverside path. This is a place blessed with abundant nature that surely gives the work a fresh, bracing stimulus.

I watched Mori as he determined a design sitting by a large window bathed in light. I had thought embroidery meant a various array of stitch techniques, but Mori insists that design is what matters most.

“I draw a lot, constantly.”

If the subject is camellias, he studies how the branches grow, the angle of the leaves, and the stages of the flowers from bud to full bloom, noting front, back, and side views. He observes branches heavy with blossoms and branches with only buds, then breaks everything into countless “pieces.” “I combine them toward the composition in my head, deciding how to place the small pieces so they read best.”

When something is missing, he draws more, linking pieces to build depth. He does not copy motifs from other motifs. He sits before the camellia itself and sketches its living form.

Even with geometric patterns, the main motif of this exhibition, the work begins by building parts. “Rather than placing them at random, I set a directional framework. The finished pattern needs stability and directness. If you place things only by feel, it collapses.”

Add, subtract, transfer, organise: he repeats trial and error, then makes final adjustments with the worn image in mind. Only then is the design complete, and his graphic embroidery, alive with generous negative space, can emerge.

Mori’s works, whose colours seem to rise with a fragrance and also move, have a compelling power that overturns received ideas of Japanese embroidery. As if playing softly in space. As if stretching in radiant arcs. As if receding toward a distant vanishing point, scattering grains of light from the tips…

He says the underdrawing is crucial for those extremely fine tips. Naturally, choosing appropriate stitch techniques is fundamental, but no matter how fine a thread you use, if the underdrawing doesn’t render that fineness, the finish will not work.

“In such cases I carve fine lines into a stencil and rub the lines on. There are limits to hand-drawing.”

A stencil for an embroidery underdrawing.

“I use them a lot,” Mori says matter-of-factly. Not in the usual efficient way of repeating the same motif, but for the sake of fine lines. Excellent makers take basic techniques as their starting line and add their own ingenuity; this cumulative ingenuity becomes a key element of personal style.

There was another intriguing ingenuity in his silk thread colours. A wall-sized thread chest in the atelier holds about 2,800 colours at all times. Rather than dyeing each colour as needed, he keeps them ready like a painter’s palette. And when he needs a colour in between two shades, he twists two threads together. This adapts an old marled-yarn method: traditional marls look overtly two-toned, but because Mori often uses transparent pale colours, he will, for example, combine a pale blue and a pale green. Then the colours and lustre of each strand reflect one another to create a new mint tone. Embroidery thread made by combining 10 to 12 filaments of roughly 21-denier silk can be split, which lets him adjust fineness and also mix colours. He brings colour expression learned from watercolour painting into embroidery by evolving traditional techniques.

While deploying a delicate, meticulous sensibility, Mori resolves embroidery as adornment for garments. Once the fabric quality, ground colour, thread colours, thread thickness and twist, and stitch techniques are set, it becomes a steady, patient task of stitch after stitch. The right hand moves from the fabric’s top to bottom, the left from bottom to top. This bilateral method unique to Japanese embroidery, he says, is a time of calm stability.

Moving his hands in rhythm, Mori watches the disposition and crossing of threads, and his heart stirs at the soft lustre and interplaying colours.

A gender-free, contemporary style

Beside Mori at work, his apprentice Michi Sato sews in silence. Ten years ago, he recruited a successor through a notice on his website. It felt bold, yet it fits an era in which truly motivated young people and masters can find each other online.

She is working on a men’s sha haori. A diamond motif, in shaded greys, is scattered across the narrow bolt. The longer I looked, the more I felt it would suit a woman as well. Mori’s designs and colours are neither too sweet nor too sharp; they have an easy fluidity that suits anyone willing to wear them. Perhaps that is why the founder of Ginza Motoji was drawn to his work. It marries impeccable skill with impeccable taste. And it is precisely this contemporary quality that makes his embroidery something people want to wear today.

MORI, Yasutsugu 森 康次

1946 - Born in Nakagyō Ward, Kyoto.

1961 - Entered the family trade as a nuiya (embroidery workshop).

1966–1977 - Studied kimono design under Kaoru Matsuo; studied sketching and watercolour under painter Mutsuko Kuwano.

1975 - Exhibited at the 3rd Kyoto City Traditional Craft Techniques Competition; subsequently entered various open-call exhibitions and received awards.

1985 - Selected for the 32nd Japan Traditional Art Crafts Exhibition (Nihon Dent0 Kogei-ten).

1989 - Certified as a full member of the Japan Kogei Association (Public Interest Incorporated Association).

1992 - Exhibited at the 12th Dyeing and Weaving Exhibition.

1994 - Exhibited at the Kyoto Craft Biennale and the 4th International Textile Competition, Kyoto.

Present - Full member of the Japan Kogei Association; Head of Japanese Embroidery Atelier Morishu.

名古屋帯

名古屋帯

袋帯

袋帯

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

浴衣・半巾帯

浴衣・半巾帯

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

肌着

肌着

小物

小物

履物

履物

書籍

書籍

長襦袢

長襦袢

小物

小物

帯

帯

お召

お召

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

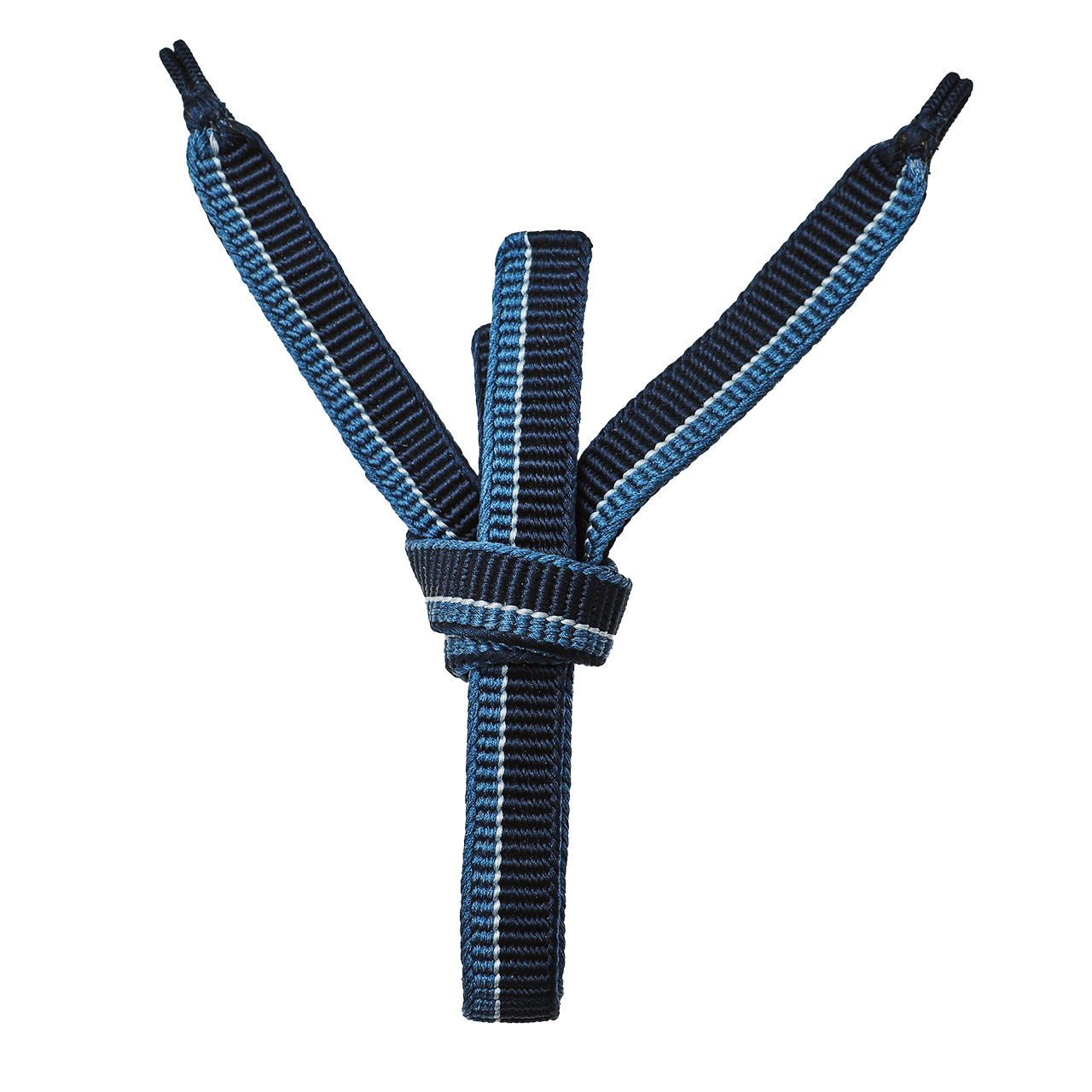

袴

袴

長襦袢

長襦袢

浴衣

浴衣

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

額裏

額裏

肌着

肌着

履物

履物

紋付

紋付

書籍

書籍